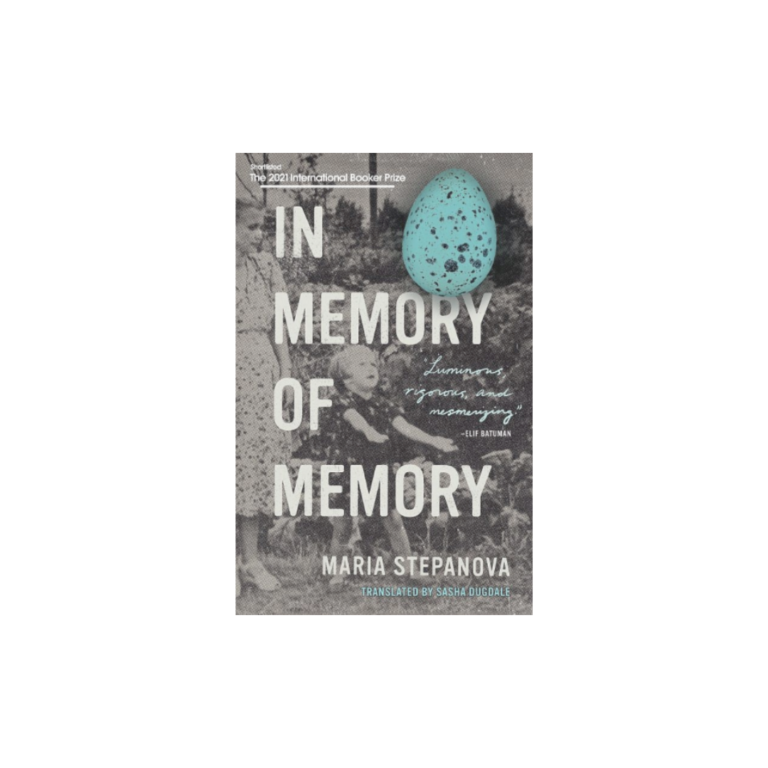

Review of In Memory of Memory

Book*hug Press. 2021. 432 pages.

“Break open a notebook at any point and be reminded of your own reality,” claims the narrator of Maria Stepanova’s In Memory of Memory. She continues: “[B]ecause a notebook is a series of proofs that life has continuity and history.” In the novel, Stepanova’s narrator dives into the belongings of her recently deceased aunt: diaries, letters, pictures, and other objects that excavate a deeply rooted past. She examines these objects and places the people that connect with them in the center of her world. How can her image of a great uncle reconcile itself with the plucky, chubby kid she finds in a decades old photograph? Stepanova grasps an ancestral past by recollecting who her family was, what they were like, and how they influence her life as it is now.

Writers have been discussing memory since Aristotle chose to pen his thoughts at a time when the idea of mapping someone’s brain was ridiculous. Generally, they have found the subject hard to pin down, yet an integral part to human existence. As Aristotle puts it, “memory is the scribe of the soul,” but Stepanova tackles what exactly that means when our memories are drastically different from who the person really was. Even today, humanity barely understands the concept of memory. Tackling the subject of memory in a novel requires a certain grace and innovation that separates one’s writing from everything that has come before. In her novel, Stepanova exhibits both, and creates a tour de force examination of how heritage reconnects with the future, reminding us all “that any point in your own past is still within your reach.”

In Memory of Memory weaves personal anecdotes, artifactual objects—photographs, letters, and odd family objects—and literary theory into a cohesive narrative. The narrator’s retrospective outlook on mortality, the capriciousness of photography, and how the past reaches ahead to twist and heave the present forward, seeps through every chapter. Some details sound ripped right from Stepanova’s life. Photographs and letters are described in vivid detail that give character to each person inside. Reading these segments is intimate in all its qualities. I felt compelled to know and understand the people mentioned. The descriptions are beautiful in how they provide personality to each individual. I’m brought into their lives as much as they are brought into mine.

Artifactual references and personal narrative are fused in the novel with theoretical references from renowned thinkers. The work of Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag, amongst others, are melded into the pages. Switching from personal stories about her life to transcriptions of letters kept by her Aunt to philosophical ideas gives In Memory of Memory an epic ambiance. Stepanova incorporates theoretical concepts to induce a broader explanation of her own theories. Stepanova’s take on our relationship to images is heavily influenced by Gertrude Stein. In a firm take on how images influence us, Stepanova references Stein’s infamous quote, stating that “photographers (and their viewers) are united by an unwavering belief in the photograph as document, witnessing reality, grasping it as it really is, without any kind of literary ornamentation: a rose is a rose is a rose.” Stepanova challenges this unwavering belief: in her narrator’s experience, personal letters and photographs reveal a completely different aunt than the one her narrator remembers. Stepanova wonders if our personal effects take a snapshot of who we’ve been, or if familial reveries reveal who we are. A past is only as concrete as its legacy, and Stepanova asks which viewpoint casts that legacy: a picture or a person. By imbuing the essays and narratives with theory, Stepanova creates new and compelling arguments about how we should view the human mind. Each chapter of In Memory of Memory carves a unique vantage point out of the stagnant cultural narratives of memory, offering unique situations that shake up the common assumptions about memory. Specifically, how stagnant it is, or as Aristotle suggested, its role as the scribe of our souls.

The past always impacts who we are. In her book, Stepanova suggests that the legacies of our present survive to influence the lives of the next generation. The actions of each individual, whether young or old, vivacious or somber, has repercussions with lasting effects. The Baby Boomers brought up Generation X who in turn brought up the Millenials who are now bringing up Gen Z. Though Stepanova’s book is focalized through personal experience, In Memory of Memory’s message is universally applicable: our history defines us. We only need to listen, or in this case, go through the carelessly kept objects of our deceased relatives. Hell, we might even find a heavily filtered selfie that completely rewires how we see ourselves. Or an old family photograph we’re embarrassed of. Either way, it’d be fun to look at.