Review of Grey Dog

ECW Press. 2024. 400 pages.

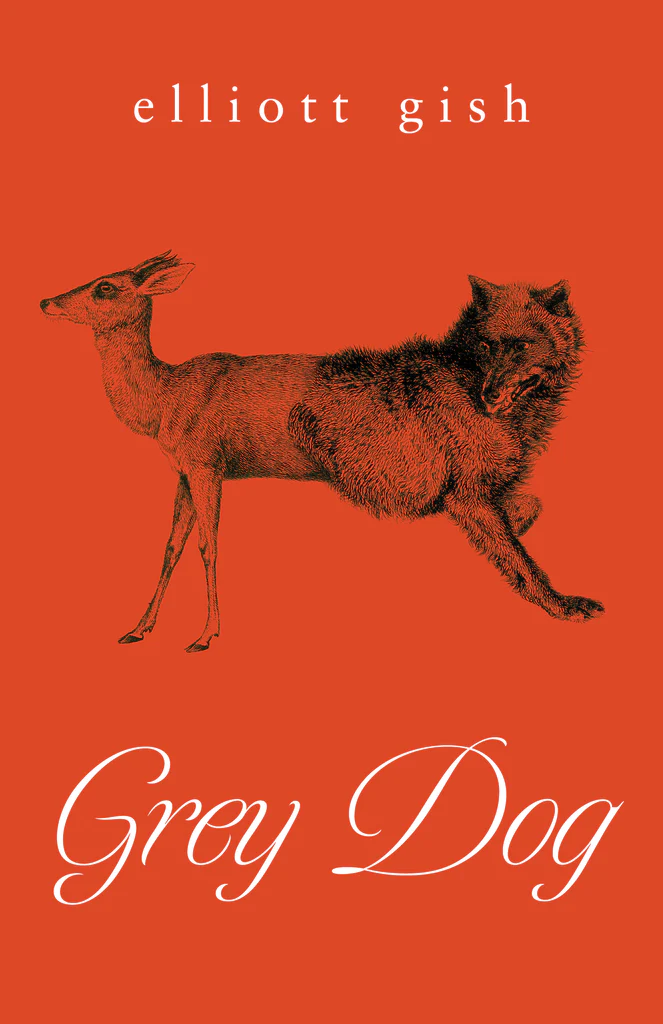

Elliot Gish’s debut novel Grey Dog accomplishes Gish’s main intention – “to creep you out.” Her book works at the unique intersection of a vast variety of genres with a familiar trope of repressed female rage and unrequited queer love meeting in the middle with grotesque bodily horror. The novel explores unconventional female urges in this slow-burn tale of abandoning society for more. The story follows Ada Byrd, no doubt named after her hyper fixation on the nature of animals, as she transforms from a meek and quite frankly uninteresting protagonist to a woman whose revealed truths and rejection of Edwardian society combine to create a compelling tale about the performance of femininity.

Gish tells the story through Ada’s diary entries, where we learn about the gray setting of Lowry Bridge and her contestation with propriety filtered through her writing. The book begins rather slow, with Ada meticulously detailing the minute details of her life. It isn’t until halfway through the novel, when Ada becomes haunted by the mysterious creature of the grey dog, that the story takes an explicit turn away from the mundane workings of Ada’s life and towards a visceral and exciting tale of female rage and horror. A must-read book for fans of Bunny by Mona Awad, and Eileen by Ottesa Moshfegh, Gish’s ability to convey female rage through bodily horror is shocking and admirable.

The novel should be most applauded for its development of Ada Byrd’s character and how it combats the archetypal scary, old spinster stereotype of the “witch in the woods.” Ada enters the world of Lowry Bridge as a respected woman who still experiences chills thinking about her own childhood experiences with the ugly and crude lady who lived in the outskirts of her hometown. This changes as the plot progresses with Ada experiencing rage against societal conventions of womanhood, and transforming from a character who blinked away her tears to one who owns her flaws and madness. Gish’s ability to mutate an uninspired Edwardian woman into a site of bewilderment that you cannot look away from should not go unnoticed. This is not to say that Gish characterized Ada as completely lifeless before page 200, but rather that she cleverly presented a mundane lady and then rapidly altered her into a manic spectacle before our eyes.

I also heavily enjoyed Gish’s description of the grotesque and her refusal to shy away from the rotten and unattractive parts of the world. This novel is concerned with integrating feminism and bodily horror, and it does so well. Even from the slow-paced beginning, Gish highlights the dirty and rotten aspects of Ada’s experiences in a way that highlights how natural these parts of life are. Gish makes it clear that she is not concerned with portraying womanhood as prim and proper, but rather wants to explore the connections of women and nature, rotten carcasses and all. A scene that stands out to me is when Ada’s friend Agatha confronts her, concerned about her wellbeing, and instead of sitting still to listen, Ada leans over, holds Agatha down and licks the sweat off her friend’s face. This gesture is doubly grotesque and erotic, with Ada leaning into her queer desires, aggressively making her fantasies a reality. Gish describes this scene with a focus on Ada’s bodily sensations – the taste of Agatha’s sweat, the urge to cannibalize her – in such a purposeful and intricate way that I was left needing to move away from my laptop to process the scene. Gish’s ability to focus on the sensuality of bodily horror in a way that explores queer desire and female urges is unique and is impossible not to admire.

The only aspect of the novel I found to be jilting was Ada’s consistency with her diary writing, even after her descent into madness. Throughout the novel it was hard not to question dialogue-heavy scenes that Ada supposedly replicated in her diary entries, or to overlook how each chapter’s end was made almost repetitive due to the diary structure, taking me out of the narrative. Gish attempts to highlight Ada’s bias in her writing, but this felt ineffective when it comes to the end of the novel. Ada continues her diary, even once she loses her mind and sheds society. Her narrative voice does not become incoherent, as I would assume it would, but stays the same as it did at the beginning of the novel, when Ada was mostly sane. The idea that Ada, in her discombobulated state of mind, would still be able to accomplish writing clear and coherent diary entries is baffling and confusing. She refuses to date her entries, but still is communicating in a written language so closely associated with the society that she completely abandons. This lack of contrast between society-Ada and manic-Ada’s writing leaves her eventual finale act to be…unimpactful? Ada’s diary in the final chapters does not reflect her mental state, and it forced me to consider a reality where one could completely lose their mind but still wake up every morning, grab a pen, and write in their journal. This idea quite frankly might be the least realistic part of this fantastical book.

Regardless of my minor qualms, Gish is still able to get across her main point: that simply being a woman is enough to drive you insane. This idea is not distinct to Ada Byrd’s world, but is too familiar to the lives we are living currently. In the day and age of situations like Roe V. Wade being overturned, we are forced to recognize the disadvantages women have in the 21st century. It has become increasingly difficult to ignore the place women in today’s society are forced into. As women today, our feelings are eerily similar to the sentiments that Ada Byrd experienced in the year 1901, and it still takes mental strength not to reject the world as a whole to live in the world and continue living our everyday lives.