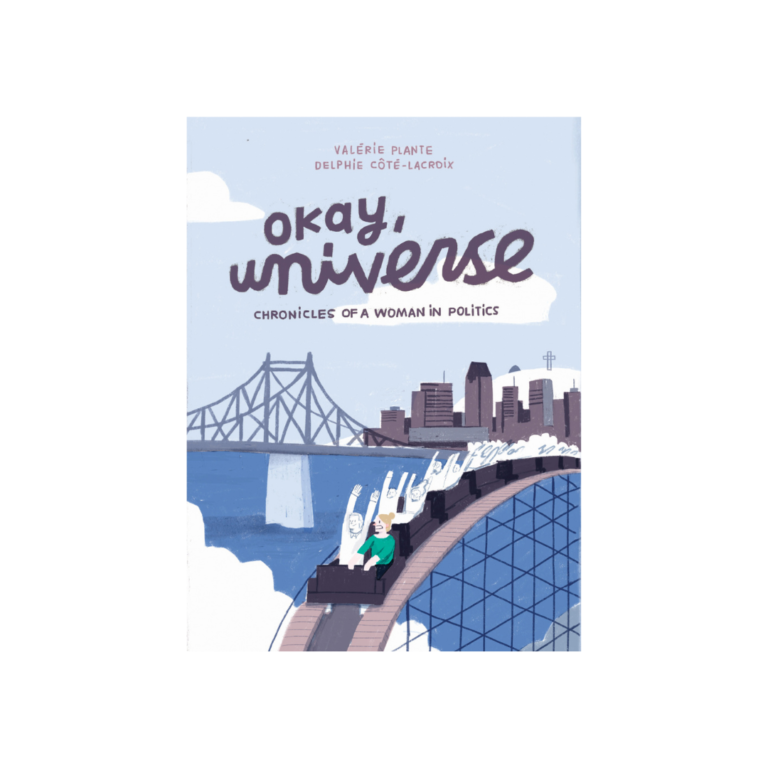

Review of Okay, Universe: Chronicles of a Woman in Politics

Drawn & Quarterly. 2020. 104 pages.

Rarely do fiction books look at local politics, favouring the spectacle of corrupt politicians like in Pen Warren’s All the King’s Men, or the grand philosophical implications of the government we live under as in Broch’s Death of Virgil. Few people talk about what it’s like to be a politician on a local level, to do the unacknowledged hard work that a city needs. The graphic novel Okay, Universe finds itself in that oddly refreshing niche, with the unique perspective of being written by the mayor of Montreal herself, Valérie Plante. Drawn in a simple but lovely style by Delphie Côté-Lacroix, this book is a surprisingly pleasant slice of life focusing on what it takes to be a municipal candidate. What it has in pleasantness, however, it lacks in deeper substance or development for those other than the main character.

The plot of Okay, Universe is pretty straightforward. Simone Simoneau, a stand-in for Plante, is looking for a new challenge in her life. This is delivered in the form of a municipal social justice party recruiting her to be a candidate. Simone jumps at the chance, though it’s harder than it first appears. She faces the challenges of fundraising, recruiting volunteers, gaining the trust of her potential constituents, and the general air of sexism she faces by simply being a woman in politics.

Simone’s struggles come off as pretty realistic. She’s a relatively normal, middle class, white woman who is entering politics for the very first time. It’s not impossible for her to do well in this field, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy. Simone’s not a lawyer or business worker, so she doesn’t have $5000 on hand for a campaign. Her friends are regular people whose life struggles Simone must consider before hitting them up for money. Having never run for office before, she has to listen to the experienced volunteers and people in her riding. At points she makes mistakes and must adjust her stance and views because of it: when she wants to improve a neighbourhood with greenery, a local tells her that improvements in housing would be far more helpful to the neighborhood’s residents. The unrealistically high standards, deriding comments, and constant underestimation or underappreciation Simone faces will be familiar to many women, especially those in male-dominated fields.

What I do like is that Plante doesn’t portray these issues as the worst thing on Earth. She shows the much harsher struggles of less advantaged people, like gentrification and high housing costs. Simone’s campaign struggles become less of a problem the more she wants to help people. And while her desire to help people begins as a foreign saviour mission, it eventually becomes more about giving the people what they need, rather than what she thinks they need. Her dedication is shown through her constant door to door work, a grueling and inglorious task. Every slammed door obviously hurts her, but she keeps going because she wants to help.

The tasks of municipal politics are rarely looked at or appreciated. It’s all small concerns in a small area. Okay, Universe invites readers to see how much those small concerns matter through the story of Simone. What are minor problems to those higher in the social hierarchy are major to those who are lower and have less means. Most people wouldn’t think twice about a nice new store in the area. But for those with low incomes living there, that means they won’t be able to afford to shop in their own area. This problem is something those who are well off, like Simone, don’t have to consider. In that way, the novel makes both Simone and the reader examine what privileges they may have. It’s an important message to send.

The novel’s problems come in characters outside of Simone. With the exception of Simone, every character feels one dimensional. The volunteers encourage and assist Simone, and don’t exist outside of the context of her and the campaign. Her family are constant, stable, supporting influences who experience little to no conflict whatsoever. These characters only exhibit traits that in some way help Simone. Any conflicts they experience are quickly resolved once Simone learns better. Beyond the way they teach and/or support Simone, they have no character. There’s some attempt to flesh out the volunteers with little bios, but three fun facts do not a character make. It would have been interesting to see the way Simone’s gruelling campaigning affected her familial relationships, or the disagreements with volunteers over policy, or low points where Simone doubted if she had support or even truly doubted herself. These smaller conflicts would have fleshed out the story and supporting characters much more.

Overall, Okay, Universe is a nice little slice of life that examines the often overlooked world of municipal politics. As the grandchild of a city politics journalist, I appreciate the way Plante shines a light on the issues my grandfather always preached the importance of. However, if you’re not interested in municipal politics, this book would not appeal to you. There isn’t a story beyond a city councillor campaign. In my experience, there aren’t many interested in that. But if you enjoy the realities, problems, and lessons of running said campaign, then I would highly recommend this short, interesting, and very realistic book.