Review of The Union of Synchronized Swimmers

Book*hug Press. 2021. 114 pages.

Can one read several stories simultaneously? This is a question I’ve held since reading Catherynne M. Valente’s “Ink, Water, Milk,” which urges the reader to do just that. The consecutively ordered ink, water, and milk sections, the narrator instructs, are happening “all at once” and “in the same place.” Reading the short story, I wondered whether I should keep the sections separate, as if they were strands in a braid? Or allow the white and clear and black to mix into a sort of murky greyness? As sparkling, inventive, and gorgeous “Ink, Water, Milk” was, I couldn’t act on the narrator’s instruction. I didn’t know how. Was it even possible?

Cristina Sandu’s The Union of Synchronized Swimmers showed me that reading several stories all at once is possible, if the narrative structure provides the necessary conditions for such a reading. On the novel’s first page, a group of girls float, splash, and play in the water. On its second, the reader realizes that said river is a metaphor, a stand-in, for something else intangible but parting: the Iron Curtain. The Union of Synchronized Swimmers is a novel in parts: a sewn-together narrative of six short fiction pieces, intersected with expository chapters that bring the six characters together. This structure allows the narrative to exist simultaneously in the past and seeming present, or the seeming present and future. In the italicized, collective-narrative chapters, the girls are training as synchronized swimmers on one side of the river, while their individual narratives show the reader what lies on the other (spatiotemporal) side of the river for each of them. Even though the stories are consecutively written (How could they not be?), because the collective chapters unfold the narrative gradually, the reader is made aware that the narratives are not to be consecutively read. The continual return to the shared timeline reflects the movement of a synchronized swim routine: an out (of limbs, heads, smiles) in unison, then back into formation.

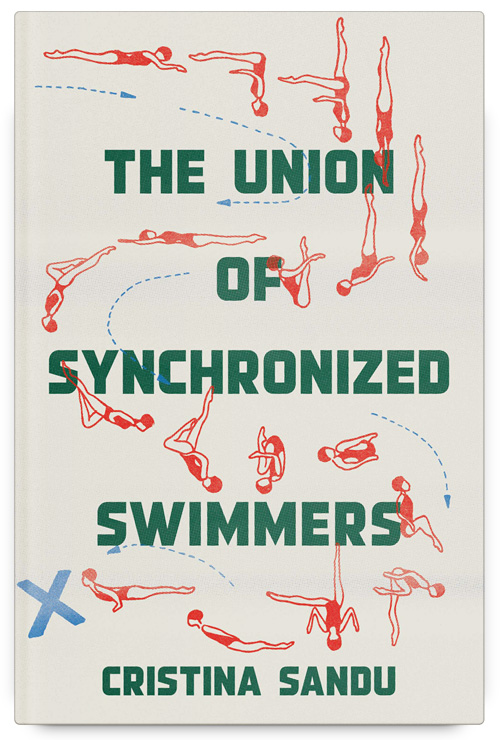

Though Sandu, unlike Valente, does not instruct simultaneous reading/imagining in her reader, the novel’s structure allows and even encourages it. This allowance is helped, too, by Tree Abraham’s thoughtful book design. Figures in swimsuits and caps don the cover, as well as the beginnings of each of the character-specific chapters. These figures, evoking motion yet frozen on the page, visually remind the reader of the synchronicity of the narratives. The Union of Synchronized Swimmers is a title that speaks not only to the novel’s content, but also its structure. It names the matter in which this novel is to be read: all at once, with each of the characters alone in the present/future, and in the space of their togetherness in the past/present. That all these readings work and may appear in the reader’s mind as simultaneous is a testament to Sandu’s craft, which also exhibits itself in the pacing of the novel.

Sandu shines in sections that push and pull. In Sandra’s chapter, for instance, the man who picks a hitchhiking Sandra off the side of the road tells her the story of the scar on his face. “A blind lion did this,” the man says, running his hand over a scar so large that it divides his face as if in two. It is a dramatic assertion, even seemingly out of place. As the reader’s mind races to lions and safaris, continues, “My old man was one of those, you know, exterminators… pesticide equipment and all.” In shifting the scale, from lions to pests, Sandu disorients the reader, dislodging them from their previous emotional state. As the man tells Sandra that his father was to treat an outbreak of ants at the home of circus trainers, the reader begins to realize what is to come, connects the dots, but that connecting doesn’t reward with a smug satisfaction, for that traversing, still, between ants and lions, keeps the reader emotionally off-balance, off-grip. It is a maneuver that Sandhu repeats throughout The Union of Synchronized Swimmers, and it works every time.

This push-pull pacing, the subverting of expectation and dislodging from emotional state, allows Sandu to write poignantly both moments of beauty and cruelty. She captures what it is like to grow up in a place and then work to escape it, what it is to hope for another life, to reap the rewards of hard labour and dedication. She also forces the reader to feel the cruelty of people in those new places: the gazes, words, snickers of people at home looking upon an outsider. In Sandu’s sharpest sentences, beauty and cruelty coexist. Lines like “They pushed each other’s heads under the water and held them there, as if performing a baptism,” “She thinks something is missing and soon realizes it’s shame,” and “This tiny detail, the end of the trouser inside the sock, is why I need to leave right now,” sparkle yet wound. In her first English-language publication (the translation her own), Sandu strikes linguistic chords that harmonize with the content and structure of her narrative.

What lends The Union of Synchronized Swimmers its strengths also presents a weakness. In the same way that synchronized swimmers donning the same cut of swimsuit, hair style, and make up may appear indistinguishable, so too, the characters of these stories, Anita, Paulina, Sandra, Betty, Nina, and Lidia, are impossible to not only separate but imagine as anything other than a single “I.” Though they are given different hair and geographic locations, their core personality is shared: once they depart from the Near Side of the River, they are A Stranger in a new land, ambitious and resilient, but homesick and guarded, subjected to the cruelties, real and imagined, of those She meets. Oddly enough, it is in the italicized chapters, home at the Near Side of the River, that the characters are most distinct, perhaps because they share a spatiotemporal plain. Once removed, their characteristics must bend to maintain the tethers. This characterization seems essential for the maintaining of structure; without it, the all-at-once readerly experience might be threatened. Still, for those readers for whom connecting with a character is the primary means of accessing a narrative, this indistinguishability may pose a problem.

Nuance is also at times sacrificed for unity. That the country is unnamed, but described in such a way as to invoke a general Eastern European-ness — from plum wine, to gossiping elderly women, to stony Lenins — allows the place to exist in an ideological, but not geographically specific way; this is the narrative of the ex-Soviet citizen, her move across the river/curtain from East to West. The mother tongue sprinkled throughout the narrative is Russian, but the country is described as tiny, pointing to any number of locations. The river could be the Neva, Narva, or the Danube, and the country any of the settlements along a river bank. The place is an abstraction, a structurally necessary metaphor that allows the other metaphors—swimming as struggle, training and synchronized swimming as the shared post-Soviet experience in the west—to work.

The Union of Synchronized Swimmers is a deftly spun narrative that mirrors its title: in the chapters the characters are together, they are most distinct, and in those they are apart, they are most indistinguishable. Sandu opts for a structure, both at the narrative and sentence level, that pushes and pulls the reader, from stillness to movement, from hope to despair, all at once, with every character as one, across time and space. In the characters, readers will not find specific people, but an essence of a person. They will lack, too, a concrete world that may be essential to find their footing. Those comfortable with abstractions, however, will find themselves here as fish in water.