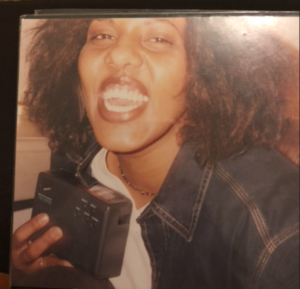

Me and my mother, August 2000.

My mother was a woman of many words, so she never sat silently through a movie. For her, watching films was a thing that doesn’t need silent observation but that welcomes conversation. There are stories I share from my childhood that are passed down from stories my mother would share with me. Memories of hers turned into memories that are now mine. I like to think she did this intentionally, as a way to ensure that her thoughts would submerge into mine, creating a past for me that I can picture easily but is best seen through her eyes. In this memory, I’m barely three years old, building a makeshift ladder of pillows and cushions from the couch, my arms so small they can hardly be classified as limbs, as I’d reach for the shelf where Toy Story on VHS stood.

Me, aged 4, watching Toy Story, 2004

Toy Story was the first film that became ours—a movie about doing your best for the ones you love most. Whether I wanted it or not, my mom and her love were bright and bold in her stride. When I wasn’t preoccupied with midday naps or pretending to read, my mornings were spent scavenging for the film, which after a few years, took permanent residency on the bookshelf in my room. The closer it was to me, the easier it was for me to play over and over, until eventually, it broke from overuse.

Toy Story became a part of my daily routine. Wake up, brush my teeth, eat my cereal, and watch my movie. Hooyo was close by, either baking, or cleaning, or singing You’ve Got A Friend in Me in her Somali accent so thick she’d leave out the “a” habitually, somehow a beat behind, despite hearing the song almost every single day for years. Most families would have movie nights that smelt of popcorn, milk chocolate, and cheap wine. Mine were spent in the early hours of the day, and smelt of çaano warmed with cinnamon sticks and freshly baked doolsho sprinkled with crushed cardamom seeds and powdered sugar for me to munch.

It was you who showed me that love can exist in forms of art.

Through bookshelves, and CD cases, in photo albums, and DVD racks.

Then, Stepmom became our thing: Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell’s Ain’t No Mountain High Enough would play through the speakers of Julia Roberts’s car. She’d hand Jena Malone’s character a stick of lipstick to try on, and they’d belt along to Terrell’s melodic voice as they cruised through the city. Susan Sarandon danced along to the same rhythms with both of her children later in the film, prancing around their home, performing their private concert for an audience made up of themselves. Hairbrush in Sarandon’s left hand, curling iron in Malone’s right, and then—the DVD skipped.

But still, I sang and danced, and twirled along throughout the living room, while Hooyo sat on the couch with her book across her lap, a smile etched across her lips. At the time, I was too naive to understand that being able to relate to something doesn’t make it reality. When I think back to moments like this, where it felt like she and I were a part of the films we watched, what I feel is a sadness that can never truly be healed. Because at nine years old, I hadn’t fully realized that she wasn’t Susan Sarandon or Julia Roberts, and I wasn’t Jena Malone. But we’d watched Stepmom so many times, it felt impossible not to think that they could be us.

“I have their past, and you can have their future.”

Julia Roberts, singing, Stepmom (1998)

My mother, laughing, 1990s

You gave me your past, so I could have a future.

But as I grew older, our conversations became shortened, the days dragging out too long. The sounds of some Disney Channel Original Movie would crackle from the TV, filling the space between us. I hadn’t outgrown Toy Story, but it felt like I outgrew her. Or perhaps we outgrew each other. The closer she’d come, the further I’d stray; further than the distance between the floor and the couch, or the couch and the loveseat. Until the space became so great that the ceiling in our living room became my bedroom floor and the levels within our home separated us. She wouldn’t have been able to hear anything with such a distance, but still, I’d watch my films with earbuds plugged into my computer.

When I utter the words “I love movies,” I can feel her voice ripple through my chest, but still it’s mine that speaks out.

I’m not sure what changed. Maybe it was me, and my clichéd teenage angst. The more I grew, the older I became, the less I felt we could relate. While her love was something I rarely doubted she had, her stubbornness and judgemental candour would manage to seep through. Soaking up the sweetness and care she intended to feed me, and leaving me with nothing but an aftertaste that was tart and bitter.

Maybe you hadn’t noticed because you were so blinded by your love, that it made you oblivious to how much it hurt me. You knew I still loved movies, but you’d never ask to watch with me. You’d linger behind, sneaking glances at the screen, or listen through the kitchen opening, but still, you’d never dare to ask.

The days blur together, and my list of movies stretch longer. Suddenly, I’m nineteen years old, and I’m tired and sad. Hooyo would ask me what’s wrong by telling me I’m losing weight. I’d tell her I’m fine. The closer she’d come, the angrier I’d feel. You aren’t listening to me. This isn’t what I want. But it’s what you need to hear, I just want what’s best for you, hooyo. Well, this isn’t it.

The air is cold in my room, or maybe it’s just cold in the film. Neil sits on the chair in his father’s office as the gun that is typically locked away in Mr. Perry’s desk drawer sits before him. I know this isn’t real, but I feel myself slipping into my screen. I look at Neil and see myself—he looks out the window, and I see the snow fall onto the trees. The branches are brittle and bend from the weight, and it feels so close that if I touch my screen, I could maybe touch them. He looks back at the desk, and my gaze is met with the gun—I see what he sees, through his eyes. I can’t remember the last time I saw a film through someone else’s eyes. Through her eyes. He’s alone, but I can feel his presence. I can feel her presence. I wonder if the chair he sits in is warm from the heat his father left behind. His hand grazes the gun, but I can feel the cold metal on the tips of my fingers, clutching the trigger. He pulls on it, and everything is black. My laptop dies.

Dead Poets Society became our Stepmom, became our Toy Story. I watched it between classes, before work, before bed. With every rewind and replay, this film became a part of me just like Stepmom and Toy Story had. Except, she’s never seen Dead Poets’ Society, and I didn’t ever ask if she would be interested. The days blurred together and our conversations got shorter. Every syllable she spoke felt like venom against my skin. The days blurred together because at this point in university, I was in a major that I hated and had a yearning in me that she unknowingly suppressed. All because she believed in practicality over passion. Neil had a passion for acting. His father believed this to be impractical and pushed him to be a doctor. I had a passion for writing. My mother believed this to be impractical and pushed me to be a psychologist. She’s never seen Dead Poets’ Society, and I still haven’t asked if she would be interested, but she was in it. With every rewind and replay, she was in it.

Our conversations become shortened because by age twenty, they are arguments. Brief, yet eruptive. The levels of our house separate us, and it’s better this way. If we existed on the same floor, I’d see how much she loved me, and she’d see how much it hurt me. Pain is never easy to overcome, but when it is birthed from a place devoid of malice, the sting lingers for longer. We just had a fight and it was vicious. You look like you’re gaining weight. Maybe you should exercise more instead of watching movies all day. She was calm, but I was explosive. She meant to be loving, but I was in pain. I don’t want her to know I’m crying. So I take a shower and let my tears mix with the water. There’s a knock on the door, and I know it’s her. She asks me if I’m hungry. Any other day I would think nothing of it. “Are you hungry?” is a weightless statement. But I know what she really means.

Do you want me to make you something to eat?: I said you’ll fail as a writer. I’m sorry for what I said.

I yell to her that I am and that I do: I am still angry, but still, I forgive you.

She hums: I don’t think you’ll fail. But, I worry. I don’t want you to get hurt.

Before I hear her walk down the stairs, I tell her thank you: I know you don’t.

Maybe I should have been more direct. Maybe I should have said that it’s her first try at life too, that we’re learning, and failing, re-learning together. Maybe I should have told her that even if we may not always like each other, it doesn’t mean we don’t love each other. That we’re connected by our genetics, yes, except it isn’t all we are. Maybe I should have told her I think film tells a story through images that move. It says what words can’t begin to form—it says “I’m sorry,” “I love you,” “I miss you,” “you’re mine.” Film connects us because it sees us and it shows us that it sees us. Maybe I should have asked her if she wanted to watch a movie. Maybe I should have said I see her. Maybe. Maybe…

But I didn’t and I don’t. Instead, I ate my rice with a side of banana and my bowl of diced fruits that later tasted like garlic, and I resumed my film alone. And I continued to watch everything else alone. But that doesn’t mean she isn’t with me. It shouldn’t mean I’ve lost her. Stepmom ended with loss, and still gave room for hope. Dead Poets Society ended with death, but the hope only caught up to me years later. I see myself in Neil, but I also see myself having another day. I see myself when I can see her.

And I see her in everything I watch.

Me at dinner, in my 20’s, 2020s.

My mother at dinner, in her 20’s, 1990s.

Andy and Mrs. Davis. Jackie, Isabel, and Anna. Sully and Boo. Simba and Mufasa. Tarzan and Kala. Coraline and Mel. Chirhiro and Yūko. Elinor and Merida. Neil and Thomas. Christine and Marion. Evelyn and Joy. I can see us in many shapes and colours.

Do you think it’s possible? That we exist in another dimension?

Tied together by the strings of our blood and DNA–

my hair, your eyes. My lips, but your smile.

Your past, but my future.

We grow apart, but still together. We grow by ourselves, but not alone.

Mother and daughter in another universe? In every universe?

Because I hope we are. I think I know we are,

and I think, no matter what, without fail,

that we will be.