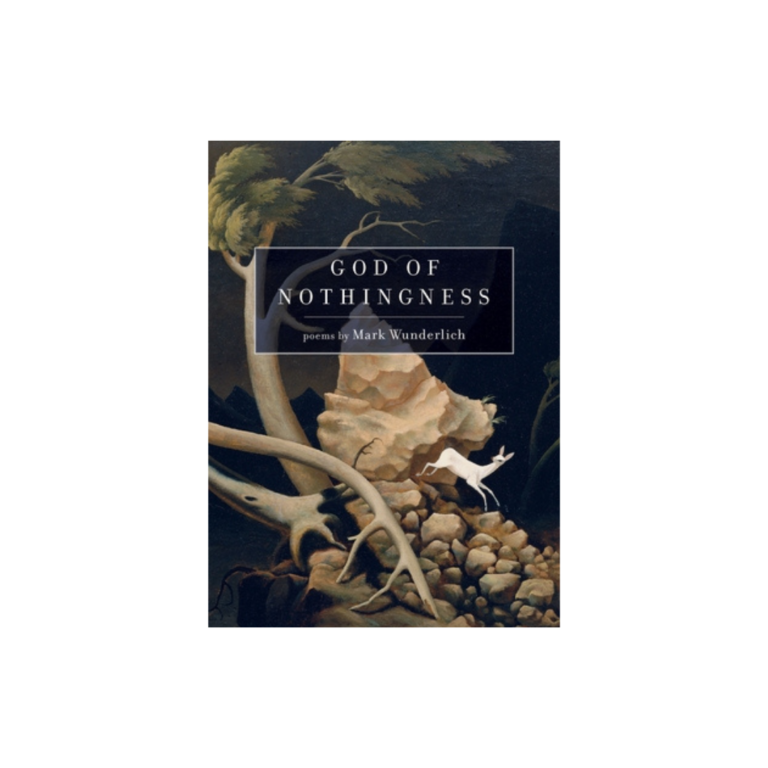

Review of The God of Nothingness

Graywolf Press. 2021. 86 pages.

Poetry is tenderness and generosity. Poetry is a soft hand that grabs you by the wrist at your favourite bar and pulls you into the bathroom to share a secret amidst the disarray of dishevelled hair and a wine stain on your shirt. God of Nothingness by Mark Wunderlich is this soft hand that guides you towards the generosity of poetry. God of Nothingness is a collection of poems that reminds readers of the reality of victimhood, suicide, and selfhood, and how they shape a man. These poems are a stark reminder of the world spinning in orbit, that the party continues even as you fix your hair in front of the bathroom mirror. These are poems of loss, of family, of sexuality, and of sensible masculinity.

The collection starts with a wondrous account of autobiography. Simply titled “Wunderlich,” this account provides insight into what follows: the overshare, what his name means, and other familial tendencies. Wunderlich invites the reader to know every intricate detail of himself and his life. His collection is conscious of his identity and of his place in the world. The poem “Proposition,” is an invite into this world, which Wunderlich depicts with a simple structure and a little tenderness. It is merely a reaffirmation that he is here, in his body; Wunderlich suggests we join him. It tows the line between the metaphysical and the gnawing existential question.

As the collection navigates loss, selfhood, and manhood, the readers earn some relief from the harder aspects of the collection: we are given five intimate stories that meander throughout various Scandinavian landscapes. These stories are rich with love, joy, and emotion carefully being thrown–like a snowball in the outskirts of Reykjavík–these stories are playful and shocking, sexually driven moments of relaxation. Interlaced with poems that praise the romanticism of Italy and the slice of life of Wisconsin, Wunderlich is guiding us throughout his life, and back home again. A great many of these poems, including “The Son I’ll Never Have,” “Elegy for a Hanged Boy,” and “Death of a Cat,” ruminate on loss; the loss of self, family, a baby lamb, and even a cat; Wunderlich knows how it feels to grieve, and he wants us to grieve with him. There is a reason why Wunderlich gives insight into the autobiographical aspects of his life, he wants the readers to experience along with him as he ruminates. The ability to recall is how Wunderlich attaches meaning to things mundane: the landscape of Wisconsin, the indifference of horses, and the visiting of parents.

There is a moment of tension between self and materiality in “On The Autobiographical Impulse” which acts to centre the reader and to treat the collection as cyclical. As Wunderlich clearly struggles with loss, identity, and what it means to be a man, the long form poem touches on these shreds, and together they act as one. It is broken into headings–or fragments–of identity and recognition of self. They stoke the flames of the metaphysical, and prompt moments of life beyond poetry, life beyond the party, and life beyond imagination. The individual pieces become whole because Wunderlich is willing to share the experiences. As the collection wraps up with “To Whom it May Concern,” Wunderlich asks the reader if his story matters and if his context matters. It acts as a letter directly addressing the reader to acknowledge the collection as whole and if it fits within the world or exists because of the world.

In his openness, Wunderlich transforms himself from a stranger to someone you think you know. The God of Nothingness ends the way it starts, with an introduction. Soft hands drag us into the bathroom, we meet a stranger and—oftentimes—we’re better for it.