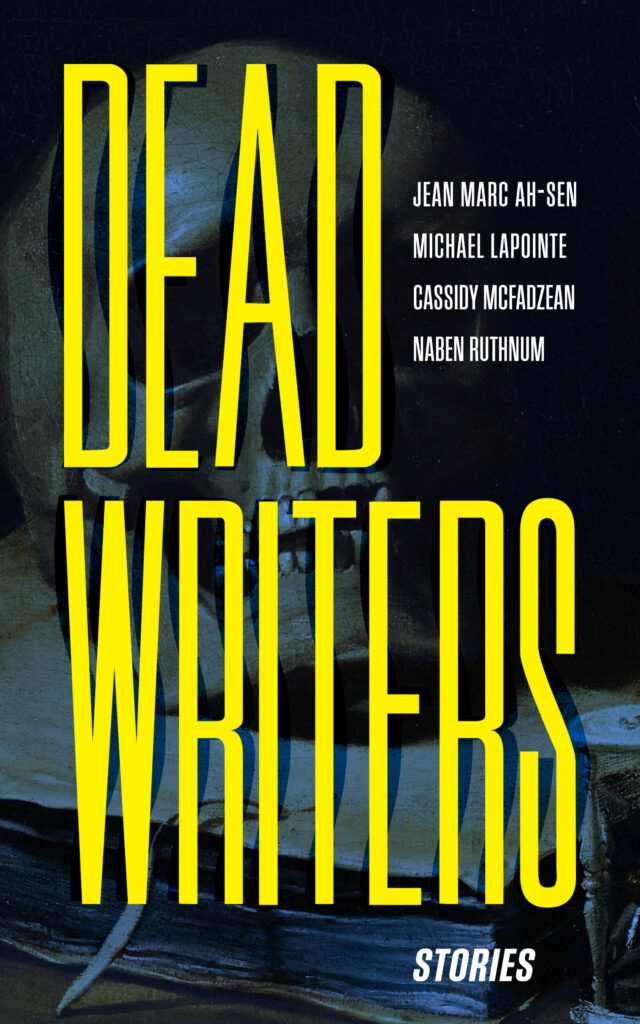

Review of Dead Writers

Invisible Publishing. 2025. 180 pages.

In Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, the devil appears in the hour of need. When the disgruntled 16th-century scholar summons Mephistopheles, an agent of Lucifer, the demon warns Faust against forsaking heaven. Yet, Faust strikes a deal anyway: his soul for unlimited pleasure, power, and knowledge. The price? Eternal damnation.

As an all-powerful demon with shapeshifting powers, Mephistopheles is terrifying. But, in the end, he is merely a servant. Critics suggest that Mephistopheles does not actively seek men to corrupt; rather, he comes to serve and ultimately collect the souls of those who are already damned. But what does damnation look like in the twenty-first century? To the modern soul, the feeling of hell is ever-present, as though our timeline were corrupted. In Dead Writers, a collaborative fiction project by Canadian authors Jean-Marc Ah-Sen, Michael LaPointe, Cassidy McFadzean, and Naben Ruthnum, the “Faustian bargain” serves as a thematic starting point for its novella-length stories. But what if the price you pay for selling your soul isn’t what you expect?

The stories largely examine moral failure as an internal struggle. Evil is not an external force leading us astray. Instead, it manifests as our inner anxieties, doubts, and desires. The stories, in turn, compel us to confront the ambiguity and moral relativism of contemporary life, raising uncomfortable questions about whether we can truly recognize evil in a world that prizes ambition over inner reflection.

Jean-Marc Ah-Sen’s “Praise Dissection Discussion Doubt” explores the tension between autonomy and corrupting influence. Our protagonist, Novalis, is a reckless journalist in mid-twentieth-century France who delivers a personal narrative questioning her life after reading British writer Stephen Potter. Potter’s satirical concept of “gamesmanship” from The Theory and Practice of Gamesmanship: Or the Art of Winning Without Actually Cheating (1947)—a deep cut, by all means–is a strategy for psychologically outwitting others to gain a social advantage. Ironically, this pursuit of dominance paradoxically leaves her more susceptible to doubt and despair—a flaw that feels especially prescient today.

In an era where reputation management pervades workplace dynamics and online interactions, Novalis’s uncertainty reflects broader anxieties about the urge to curate an image. Ah-Sen’s exploration suggests that the more we attempt to control perception and gain an advantage, the more vulnerable we become to self-doubt, isolation, and paranoia.

Besides being one of the finest stories in the collection, Ah-Sen’s piece also reminds us that this is a collection about writers—people whose thoughts are most effectively expressed on the page. If there’s a unifying quality among these stories besides the Faustian bargain, it’s that the collection’s authors share a gift for character-writing, creating a delectable ode to the neurotic. Whether they’re writing about death, dismay, or, better yet, coming to terms with the limitations of life, each author helps us recognize that we are similarly flawed.

Life is framed as a test of our resolve, played out within the colossal hell of human consciousness. However, this complex setup has its limitations. Don’t get me wrong, life is hell. However, the collection rarely seals the Faustian deal. In Marlowe’s version, the stakes are clear: Faust knowingly exchanges his soul for knowledge and power. As his time runs out, he becomes increasingly desperate and regretful. Despite pleading for salvation, demons ultimately drag him to hell when his contract with Lucifer comes due.

In Dead Writers, the stakes are unclear, as is the actual bargain. Life is full of moral compromise and exchange; sometimes, we feel the consequences of our actions and other times, we don’t. The absence of a clear reckoning or catharsis may reflect a broader cultural disconnection from ideas of accountability. (It feels like the bad guys keep getting away with it, actually). However, the stories risk alienating readers who seek narrative closure or a sense of ethical clarity. How do we know when we’ve truly made our Faustian bargain?

Novalis’ desire for artificial social control blinds her to the moral compromises she makes. Despite the pain and paranoia, she neither learns nor directly crosses any threshold but continues her narration (delivered inside a tavern) ad infinitum.

Cassidy McFadzean’s story, “Getaway for Peace and Tranquility,” follows a Toronto couple vacationing in an Italian guest house. The couple experiences supernatural, near-death occurrences while observing architecture from sometime between the collapse of the Roman Empire and the beginnings of the Italian Renaissance. Anxiety and existential dread permeate the story as the couple self-reflects amid a terrible vacation (à la season two of The White Lotus). McFadzean’s story, which begins with a quote from Aldo Rossi’s A Scientific Biography, nicely blends themes of location, history, and architecture to create a foreboding presence.

Yet, instead of looking inward, the couple is absolutely fixated on the corrupting influence of their Airbnb host—who must be responsible for their terrible vacation. Their unease grows as the host’s cryptic remarks and eerie nocturnal habits suggest she knows far more about their misfortunes than she lets on. As their paranoia mounts, they begin to wonder if their host is merely strange—or if he has been orchestrating their entire ordeal from the start. Otherwise, why would they not be having a great time?

The couple’s obsession with blaming someone else rather than taking personal responsibility sets them up to be deserving of a good scare. At the same time, they haven’t really done anything wrong. I’m left wondering if the authors actually care about the collection’s theme. Of course, Faust did not claim personal responsibility for his ills–and wasted his power on trivial pursuits–but at least he paid the ultimate price.

The standout story is Michael LaPointe’s “The Events at X,” which comes closest to interrogating the limits of moral intention. In 1921, Dr. Sidney Lawrence, a poet and physician, is stranded in a remote community while travelling with his friend. Lawrence treats a group of Indigenous children at one of Canada’s residential schools, where he witnesses colonial evil take place firsthand. Dr. Lawrence learns the students have been poisoning themselves, as “they’ve been taught it’s better to die than to submit to the white man’s religion.”

When a student named Edith dies trying to escape, Lawrence is overcome with guilt and succumbs to the same illness afflicting the children, losing his vision. His guilt, centred on his emotional journey rather than the systemic horrors faced by the children, sidelines the real trauma of colonial oppression. LaPointe writes of his moral corruption with poetic precision, bringing the devastating consequences of residential schools into focus.

Each author delivers anxiety-inducing, thought-provoking stories about moral corruption, betrayal, and the perils of ambition. Despite exceptional writing and compelling characters, the collection doesn’t invoke much feeling, leaving a blank space within the reader. While some narratives lack clarity about their stakes, the collection does powerfully explore the dangers lurking within us and perhaps the bargains we make with ourselves. In other words, the devil you know is not always better than the devil you don’t.