Review of Green

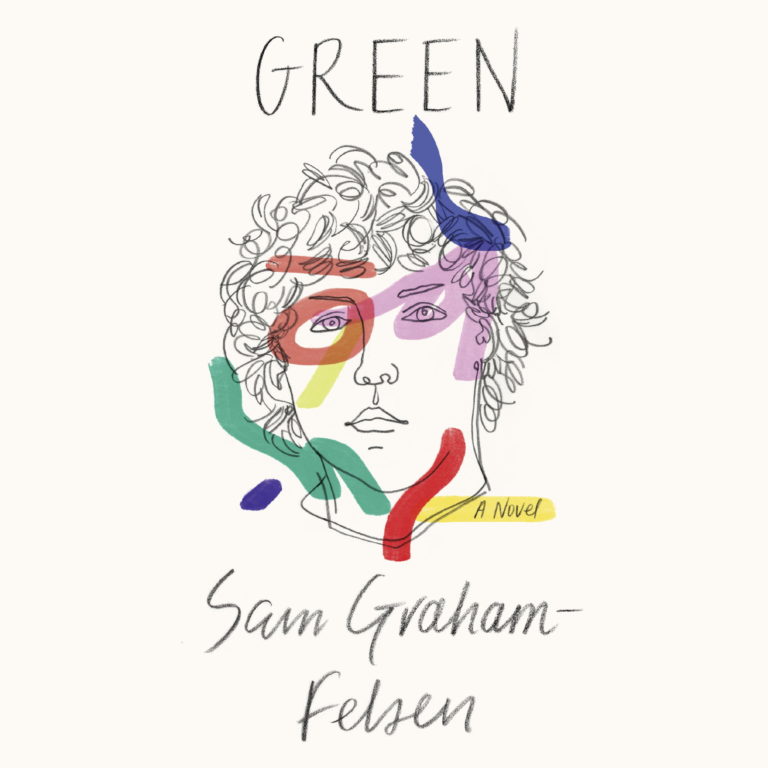

Penguin Random House. 2018. 320 pages.

For a rookie novelist writing a coming-of-age narrative set against the racial unrest of a 1990s’ Bostonian backdrop, Green has an apt title. It is this self-reflexivity that epitomizes Sam Graham-Felsen’s novel, whose bildungsroman recounting an interracial friendship between David, one of the two white boys at his middle school and Marlon, a die-hard Celtics fan and loner, is analogous to Graham-Felsen’s youth growing up white in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood. Green hinges on the binary of success and failure, as the bildungsroman and racial bias tend to revolve, but this time on a pre-pubescent, secondary school scale. Both Dave and Mar contend for a spot at Boston Latin, one of the best high schools in the city, a conduit to Harvard, but moreover, an escape from Martin Luther King, Jr., Middle School, where Dave is known as a “Caucasian catastrophe” and Mar, as an outcast with an addict-mother (11).

Having stood at the helm of the first presidential campaign to mobilize supporters using social media, Graham-Felsen knows how to appeal to an audience. In Green, Graham-Felsen makes what appears to be a very conscious decision to demonstrate how 12-year old boys speak to each other—in public, and in private. For one, they don’t say “Awesome,” and they don’t give high fives, two mistakes Dave makes on his first day at Martin Luther King Jr. According to Dave, “high fives are some hiked-up-shorts Hoosiers shit, the physical equivalent of awesome” (11). It’s these kinds of idiomatic slip-ups that make Dave’s “curly blond hair, pink cheeks, and pale blue eyes” a shade blonder, pinker, bluer, whiter (8). As one of two white boys at Martin Luther King, Dave unconsciously uses black vernacular at school and around his black peers (except Mar) as an adaptation to the environmental stress of being not only white, but mediocre. To read Dave converse with his peers as if he’s the fourth member of Geto Boys, his favourite rap group, is excruciating and yet entirely evocative of the reader’s own cringe-worthy middle-school performance, a three-year production that determined one’s clout for the main event, high school.

With Mar, a fellow Celtics and Larry Bird fan, Dave lets his guard down for the most part. The friendship includes what you’d expect from an interracial coming-of-age story; Mar disproves of Dave’s ignorant premises about blackness and the projects and Dave introduces Mar to the blindingly-white world of musical theatre (139). Where it deviates is with Graham-Felsen’s inclusion of “the force”, the term Dave uses to describe the implicit racism he feels. The force “isn’t some Jedi bullshit; the force […] is real, and its energies are everywhere, working on everyone” (31). It’s the force that affords Dave a pass when he’s caught cheating on Mar for the entrance exam to Boston Latin, a blind eye to the swastikas he draws in his notebooks, and a spot on the Boston Latin waitlist. It’s the same force that deters Mar’s own acceptance and symbolic success in America—a barricade on the path to Harvard; to a nice, white life.

Green isn’t subtle about the message it’s after. In a frustrating final scene, Dave struggles with his status as not just a “white boy” or a “whitey” but a white person (296). “I will be surrounded by dudes like this, […] who grew up with no idea, for the rest of my life” (296). With this, Graham-Felsen admits that he too, has no idea. It’s these kinds of disconcerting moments that make the novel’s reader green, that spark a hyperconsciousness of the seemingly mundane privilege white folks naively enjoy, but rarely acknowledge.