Review of Anecdotes

Book*hug Press. 2023. 265 pages.

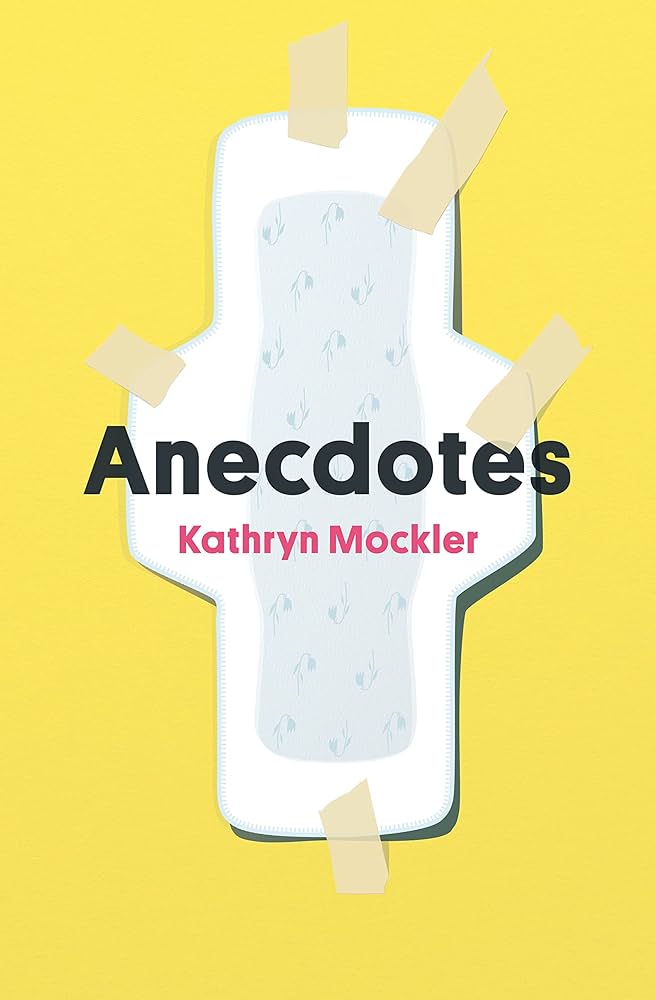

For nearly 20 years of writing, Kathryn Mockler didn’t think twice about discussing periods. But her debut collection of short stories, Anecdotes, is treading new ground and opening up a conversation about shame culture. From a young age, we’re taught as women to hide tampons in the sleeves of our shirts and to attend to cramps as minor headaches or ankle sores; to keep our composure and deal. Last week, my coworker told me she had never experienced cramping before. But her last period had triggered pains so badly that she took herself to the hospital because she was scared. Illustrator Malcolm Sutton, who edited Anecdotes and designed the cover, selected a maxi pad taped to the wall as the feature image, animating Mockler’s short story “The Pad.” She writes, “It is a beautiful work of art” as she sticks the sanitary product up in her bedroom, admiring it proudly. On a recent trip to Amsterdam, I had an argument with a girlfriend about oversharing. I had gone into detail on a first date about using a tampon, which he had described as “gross” and quickly changed the conversation. This made me feel insecure about my body, but simultaneously frustrated over something out of my control. I felt dirty, tainted and undesirable. But as Mockler valiantly conveys, calling attention to what is often shamed – to call it beautiful – feels empowering.

Mockler writes three more stories about periods in her collection, but this concept of shame is one that’s recurring in many of the subjects she covers, connecting it to “alcoholism, harassment, sexual abuse and disfigurement.” She mostly focuses on this in “We’re Not Here to Talk About Aliens,” one of the four sections the book’s split up into. She writes about having a disfigured eye and wearing sunglasses to cover it up. She shares stories about being left alone in dark corners with male professors, hotel guests and egotistical bandmates that feel suffocating. Her dark humour and sharp delivery eases this unsettling feeling and allows us to cope alongside her.

This collection comes at a time more relevant than ever for rectifying shame with Yorgos Lanthimos’ release of Poor Things this winter and the phenomenon that followed Greta Gerwig’s Barbie. Both films proposed an alternate fantastical reality—where women, specifically, could navigate the world free of perception. Mockler’s honest and moving depiction of childhood bluntly reconstructs that transitional period when we discover our bodies are looked at, analysed and sexualized. How they’re desirable and how they make us feel weak. She thoughtfully exposes how content we are with embracing ourselves until someone tells us it’s wrong to do so. And she’s as brutal as she is unforgiving because holding onto that shame is exhausting. Mockler’s prose allows us to grieve our youth; to visit those parts of ourselves that felt powerless and give them somewhere to lay their head. “I don’t want to be a woman!” she puts indignantly. It’s that outrage born from shame as our sense of self shifts. When giving voice to negative emotions around experiences that reveal a great deal of pain – they’re often overridden by a paralyzing fear. Mockler teaches us to trust the transformative process, which reveals a commonality in our repression of these difficult emotions.

She warns us we’re not immune from the larger societal and economic consequences of climate change. Earlier versions of “This Isn’t A Conversation,” a one-liner poetry series, appeared in the Guelph Institute for Environmental Research’s Micro-Climate Stories. Certain excerpts have also been adapted into short experimental videos. This sobering conversation, along with other absurdist flash fiction in “The Boy is Dead,” paints us a frightening picture of the pressing reality of the ongoing climate crisis. Satirical but poignant, this piece confronts denialism. And yet, Mockler’s writing is brimming with guilt and acts on emotion. Her crass and blunt remarks express regret. It’s that feeling of helplessness when you can predict what’s ahead, but have absolutely no control over it and the anger that comes out of that. It’s difficult not to get emotional when our contributions seem useless. How do we act justly on behalf of our earth amid political outrage? Mockler creates a space for us to have this reaction and encourages us to not disembody ourselves from the narrative entirely. We’re all deeply interconnected with each other, especially with those we disagree with. It’s more important than ever to expand our capacity and to keep engaging critically.

We become easily overwhelmed by the prospect of not being able to find our way back to happiness. At this intersection of agroecology and feminism, Mockler cleverly ties this habit of repressing these negative feelings with speaking about the environment. Once we uncover those emotions, we have to face the truth. And it’s the same with how we approach conversations about our planet. It’s how we confront our guilt. By reshaping the way we have these discussions and approach healing generations of damaged ecosystems, by default we could encourage new growth within ourselves. Maybe the root connecting these processes of growth will aid in confronting our pain and allow us to flourish.

Perhaps, having a period enlightens us to reconnect with the body and the natural world. In this junction, Mockler illustrates how, although aspects of humanity are going extinct, it’s these small rituals like taking care of oneself and one’s period that feel the most human. The colonial narrative is one that attempts to remove us from our connections with nature. In our very treatment of the planet, we’re disrupting nature and the natural process of our world. And so, menstruation is rejected in relation, as it’s a natural process of the body. To return to this is to re-embody a wildness, rise above shame and to tend to ourselves and our wounds.

Continuing this pattern and reminding us of this need to reconnect, she segues into this hybrid collection’s final section, “My Dream House.” Concepts of time personified ponder our existence and get to work on building their dream home. A utopia that’s safe, accessible and not on the verge of collapse. But they’re laughed at, ridiculed, humiliated and the house never gets built. Mockler cleverly relays here that we’re so influenced by our past and our future that we remain stagnant. And how we may feel suffocated until we begin the work of confronting our hurt and our shame and transforming that to caring, constructive action. That’s action within ourselves; the land we inhabit; and have made a promise to care and nurture for. Her abruption of this silenced upbringing is radically transformative and is a call to action to all who will listen.