Review of The Acid Room: The Psychedelic Trials and Tribulations of Hollywood Hospital

Anvil Press. 2022. 160 pages.

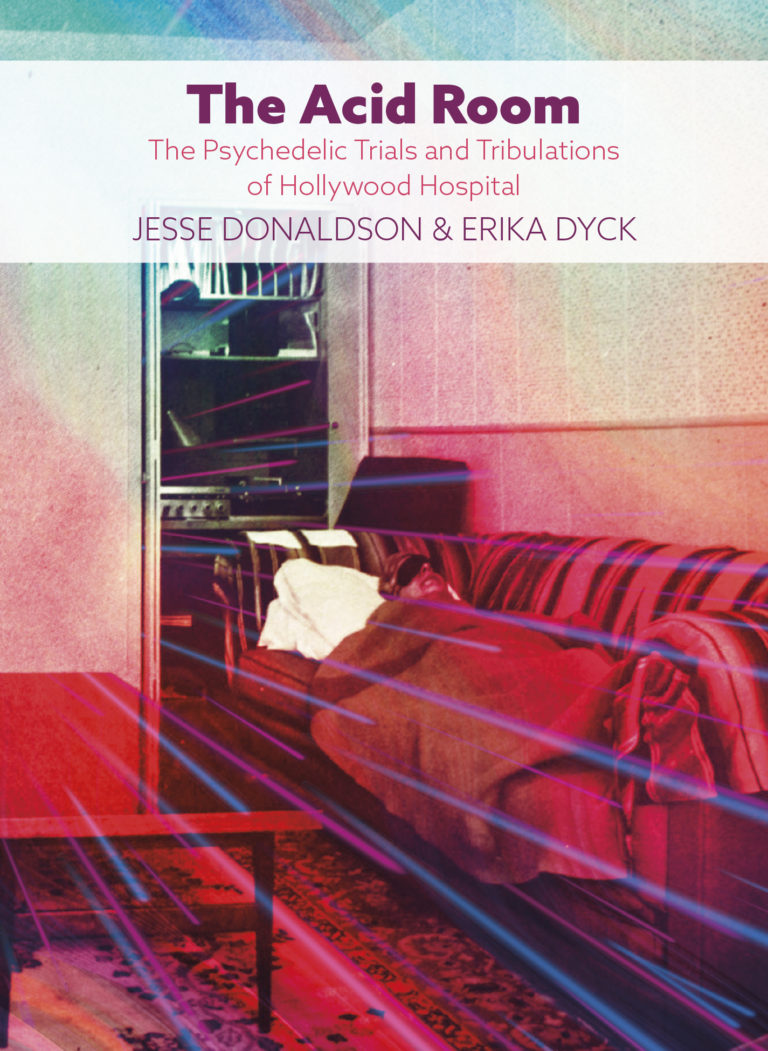

Being enrolled in the History of Madness course at Toronto Metropolitan University, I have had the wonderful opportunity to gain a critical understanding of the medically-modeled world of mental illness, addiction, and madness. A major point of contention in this area of study is the oppressive nature of the hegemonic structure surrounding these matters. Specifically, its seething desire for normalcy, where a ‘well-functioning’ society often takes precedence over the needs of the individual. The Acid Room offers a similar challenge to the various pitfalls of the medical world. Jesse Donaldson and Erika Dyck’s historical non-fiction book is an exemplary narrative detailing New Westminster’s forgotten Hollywood Hotel, once a mecca for psychedelic discovery between 1957 and 1968. The authors explore the socio-political controversies surrounding the incredibly progressive form of psychedelic therapy the facility offered in its infamous Acid Room. In their book, Donaldson and Dyck challenge the scaremongering and prohibition of Lysergic acid diethylamide (commonly referred to as acid or LSD) throughout the 1960s, which society was quick to label illicit and dangerous. With The Acid Room, the authors return to the precipice of psychedelic explosion and its consequential illegalization, working to deconstruct the social forces that can often work against public interest, social equality and mental well-being.

At the heart of Donaldson and Dyck’s book is the steady assurance of psychedelic therapy’s life-changing effectiveness. They weave us through the harrowing journey taken by psychedelic drugs, which have faced everything from academic wonder and cult followings, to false accusations and public scrutiny. They argue that this journey has led us to the world we live in today. Before the prohibition of LSD and other psychedelics, trials and experiments elicited imperative discoveries in the world of mental illness, addiction and science. The authors detail an important critical narrative, working to reveal the delicately balanced processes of medical science discovery, in the realms of public relations and politics.

Donaldson and Dyck offer rich portraits of the colourful characters who were part of this psychedelic explosion. There were the strictly academic figures, those with personally motivated interests, and the almost villainous critics who pushed against psychedelic use. Each force influenced in their own way the fate of LSD and other psychedelics. Arguably one of the most important individuals in this movement was Alfred “The Captain” Hubbard. Once living the fast-paced, dodgy life of a bootlegger, he soon turned his interest to psychedelics. Hubbard is a key representative of the battle between academia and personal interest. From his fervorous desire (bordering on obstinance) to enter into the world of psychedelics, to his ultimate financial demise and exclusion from the academic community. Hubbard exemplifies the fine line that existed between legitimate scientific exploration and over-zealous supporters of the movement, the latter of whom often tried to advance the use of psychedelics by any means possible. Individuals like Hubbard also illustrate the seemingly inevitable shift of LSD from medical use to the furtive realm of “explorers,” people experimenting with psychedelics recreationally who were perhaps too little aware of its associated dangers. The impending doom of psychedelics has become a familiar story, though Donaldson and Dyck provide us with another side of the narrative, one which is too often overlooked. The subject matter they are working with is incredibly controversial, propagating major points of contention during the 1950s-60s. Their portrait of psychedelic study and exploration, however, boasts high success rates and seemingly miraculous cures of major mental afflictions from both patients of and those who had brushes with the Hollywood Hotel. I believe these findings are especially timely given Canada’s current revisitation of psychedelics in the medical field.

The Acid Room is teeming with historical facts, though the narrative unfolds smoothly in an enjoyable way. Donaldson and Dyck do a wonderful job of weaving factual information with an excellent variety of narratives. They include real success stories of various patients from the Hollywood Hotel, excerpts of letters between key figures, and short epigraphs at each chapter from ex-patients detailing the feelings and emotions they experienced throughout their treatments. The accounts of ex-patients are both harrowing and heart-warming tales of success; they were people who were able to turn their lives around drastically with the help of psychedelic therapy. What could quickly turn into a dry account of a major movement is instead effortlessly developed, as the authors’ competent ability to weave compelling stories with fact offers readers a refreshing narrative. Through this structure, Donaldson and Dyck avoid overwhelming readers, even those who normally avoid non-fiction. These interspersed stories have an additional effect, they effectively challenge any commonly held notions an individual may have concerning psychedelic use. Their tales offer an alternative way of thinking about these substances: not only as something recreational, but as an incredibly powerful therapeutic tool.

Donaldson and Dyck do a fantastic job of detailing the battle between the academic world with that of the fantastical explorers and critics. While these forces often intermingled and bled into one another, there was eventually a push to distinguish the two groups from one another. Academics expelled the explorers (such as Al Hubbard) from their circles in an attempt to legitimize psychedelic therapy to the growing concerns of the outside world and negate the accusations of critics. The duo’s narrative effectively re-examines the decision to illegalize LSD, while paying tribute to the academics who vied to keep psychedelics in good standing and away from the calamities of prohibition. Donaldson and Dyck further indicate that even the most stringent of critics did not want prohibition as their final goal, but by the time they realized the direction the movement was going in, it was “too late” to backtrack on their overzealous critiques. The public relations damage had been a disastrous success. The Acid Room thus calls into question the illegalization of LSD, bringing to light the muddled confusion surrounding its progress in both the social and medical world.

As previously mentioned, a key element of The Acid Room is the manner in which it challenges commonly held notions of psychedelics as a therapeutic substance. There are deeply imbued prejudices and fears surrounding LSD and other psychedelics in our contemporary society, but Donaldson and Dyck do a very thorough job of challenging these ideas by returning to the early ages of scientific discovery and exploration. The authors work to deconstruct the long-standing public relations nightmare surrounding these substances. Though it is not only through their fair depiction of this movement that Donaldson and Dyck work to change our minds, as the personal accounts of highly successful Acid Room treatments provide us with a staggering realization of psychedelic therapy’s effectiveness. Their account of the prohibition offers readers a complete and accurate narrative of the events leading up to the illegalization of psychedelics. When you read all the success stories from Hollywood Hospital, it’s difficult to imagine how psychedelics suffered such a terrible fate. Through these success stories, and the plethora of medical and academic support outlined in the book, The Acid Room shows us the reverse side of moral panic and prohibition; we are given a story that can make us question any preconceived notions we may have about psychedelics.

Thanks to Canada’s re-legalization of psychedelics for medical use and the renewal of psychedelic exploration, this book comes at a pertinent moment in time. In the light of shifting perspectives around the use of these substances, the reader is given an opportunity to delve into earlier usages of psychedelics. From Donaldson and Dyck’s account, we see how Canada has historically been involved in innovative medical models, being inclined to break the mold of standardization. Fortunately our perspectives are shifting; however, there is still much work to be done, as a traditional medical-model is still deeply rooted in our society and understanding of treatment plans. The Acid Room helps break apart long standing prejudices and perceptions around the medical benefits of psychedelics. Eligible individuals may now access prescriptions to psychedelics, due to shifting perspectives toward the efficacy and safety of these substances. This book ultimately does very important work, bringing a historical account of medical science development to various audiences in a fascinating way.