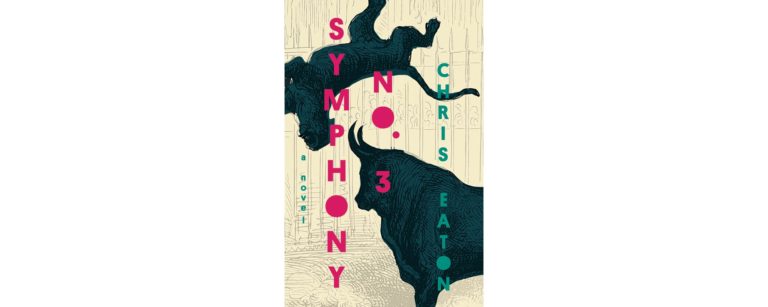

Review of Symphony No. 3

Book*hug Press. 2019. 360 pages.

“Some creatures don’t deserve to live; those without use, which should go without saying, but also those who are too useful, because they rob us of the opportunity for our own use […] the opportunity for purpose.” So begins Chris Eaton’s monumental novel Symphony No. 3, a novel whose writing style, and ambition, rivals the canonically “great novels” of the nineteenth century by reviving their approach to storytelling in the twenty-first century. As a partially fictionalized account of the life of French composer Camille Saint-Saëns, the novel is told through his twin brother, whose existence is ambiguous, as Eaton drops hints over the course of the novel that keeps us questioning how the narrator can be “an orphan with two mothers and a father, the brother of an only child.”

Symphony No. 3 is a literary marvel that requires a very patient reader, someone who will make it through all the stories-within-stories, lengthy asides that often take up entire chapters, and dense descriptions that are picturesque and horrifying in equal measure, and come out without skipping a beat. Yet, not everyone will be able to stomach the lengthy and graphic paragraph only a few pages into the book that describes Saint-Saëns being killed and turned into human taxidermy on a balcony. This episode is one of several terrifying passages that spring up like mouse traps without warning, leaving the reader with no choice but to face them head-on.

Divided into four sections that reflect the four movements of Saint-Saëns’ most famous work Organ Symphony — allegro, adagio, scherzo, and finale — the novel embodies their significance in the music world both through the events of that particular section and Eaton’s writing style. The second half of the book, however, loses momentum and the level of engagement it had in part one. The musical staff with a rest that separates each half feels like an ominous warning of a sharp change in pace. Similarly, for those who, like me, were captivated by the opening few pages in which Eaton lays out the theory that “everyone in this world is either a camel or a lion,” there is a certain disappointment in finding the theory is left with no satisfactory conclusion.

Eaton is a skilled writer, of that there is no doubt. Yet, over the course of the entire novel, I found my admiration for the writing overshadowed by how much I struggled to process what was written. Not only is Symphony No. 3 slow and meandering, but the pacing has also made it easier to notice the novel’s shortcomings. The most significant of these was Eaton’s treatment of race, as it is not always clear whether he is actively condemning this kind of racist and colonialist rhetoric, or if it is simply used as a decoration to add realism to the novel, evident in one character’s disturbing statement that “Perhaps it was the lack of a written culture that had made the Arabs so violent.” As a result, my opinion of the novel was best captured by Saint-Saëns when he declared: “Someday, some future [musician] will be born who will be able to play this […] For now, the piece can wait for him.”