This essay is supposed to be about Joyland Park. A bowling alley called Joyland Bowl carried on its name—nearby—when the park closed in 1962. My plan was to write this at the bowling alley bar. To get a sense of the place now (the bowling alley is near where the original park stood) and then to follow the traces that remain down through the spiral of time. But I drove there and Joyland Bowl is now also closed. Has been for a while. When I first wanted to write this essay—two years ago—it was open. I am disappointed in myself for waiting too long, and in the lost opportunity of the essay I wanted to write. I will have to write a different essay now.

I’m writing this on a black notepad in a mexican restaurant bar in a part of Lexington, Kentucky called “little Mexico.” I’m drinking a michelada from a tall glass. This essay was to be a centerpiece of this collection.

This building used to be a Frisch’s Big Boy. It’s obvious when you look around. The old vinyl lined booths remain. Just a couple years ago, the salad bar island remained. I’m the only white person here. I’m drinking the michelado fast. I’m writing fast. My handwriting is messy and all caps—I copied this from my dad and feel it makes my handwriting less messy and child-like. I’m pissed off. Pissed off that Joyland Bowl is closed. That I waited too long. That I missed the opportunity to write the essay I wanted.

What happened is this: I drove to where Joyland Park used to be. I had an inkling even the bowling alley was closed. But one Google Map result showed it open. Trip Advisor reported it closed. Trip Advisor was right. Had been right for a while.

***

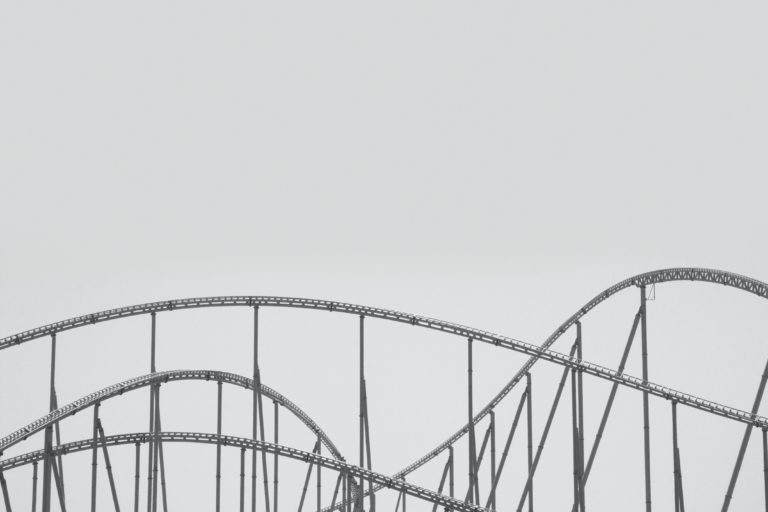

I drive around the neighborhood where Joyland Park used to be. Everything is rundown. A gray quiet hovers. Small houses run along disrepaired sidewalks, which lead to an old plain box-shaped apartment building with off-white stucco walls, and wood balconies filled with plastic chairs and plastic kids’ toys. I turn around in an empty neighborhood park with swing sets and monkey bars. Along the sidewalk, a boy with blonde hair pushes a yellow cart. I drive back to where Joyland Park’s dance hall, pool, and roller coaster had been. Near where its distant relative—and namesake—bowling alley had carried on. All that remains is a large open parking lot. Semi trucks sit parked, filling half the lot. I park beside a nineties era Dodge Dakota Sport pickup truck: red with orange blotches—camouflaged for the sun. It’s the middle of November. It’s cool, not cold. It’s too bright out. Sun beams tear through my passenger window. They make me squint. I recline my car seat. I feel very tired. I don’t know what to do about the essay. Or the afternoon. I can’t write it in the bowling alley bar—that distant and once living relative of the place and time I want to understand. That’s for sure. I close my eyes and lean back in the car seat. I’ll figure it out later. After I rest. I rest my left arm behind my head. This is no place to write, I think. My arms and body ache. I have plenty to worry about. Like a body of water with a calm opaque surface and circling sharks beneath, out of sight. I feel sleep pulling me under. I let it.

I wake up after dozing a few minutes. I think about dozing off again. The parking lot light flicks on, and evening creeps in.

Time to move on.

I drive down North Broadway, past I64 exits. Through town.

I pull off at a sports bar. I smoke a cigarette standing in the parking lot. Smoking alone always feels lonely. Maybe that’s because smoking has always been social for me. Maybe it’s other associations. Maybe that’s for another essay. I flick my half-gone cig into the parking lot asphalt and walk toward the bar. I stop and let a car go by on the narrow street I’m walking down.

I walk into the bar. TVs blare football from every angle. I don’t like how it feels here. It feels uneasy, too bright, too frantic, bad music. I use the restroom and walk out, back past the hostess I’d just walked by a moment before. I hold my phone to my ear like I’m taking a serious call.

No one’s talking in my ear.

I drive down Harrodsburg. The day is giving way to night.

That’s when I decided on the Mexican joint.

The bartop is painted with tropical colors—images of bright tropical fish and turquoise waters. The wall behind the bar is painted turquoise with painted sharks and fish swimming by. It feels like you’re underwater or in a large aquarium, sitting at this end of the bar. The waiter brings out a super red burrito—pork wrapped in a tortilla, covered in melted monterey jack and red ranchero sauce. He brings a plastic squirt bottle filled with homemade green hot sauce. First time they’ve done that. I used to come here so often that they gave me a free beer on Cinco de Mayo. It’s a good place to come alone. The booths can hide you, the bar is underwater, and the music is always in Spanish. There’s always soccer games on the TVs, and the commentary is always in Spanish. It’s usually not crowded. The lights are low. The food is good. The prices are reasonable. It’s in a rundown working class neighborhood. I feel comfortable here. Sometimes, after I eat, I’ll walk around the neighborhood.

A couple of Mexican guys sit down next to me at the bar. They mostly speak in Spanish. One wears a big white cowboy hat. The kind a Texan rancher wears. The other is short and talkative. He says hi. I respond. He asks what I’m writing. I tell him just a sketch. He asks to read. I say it’s not ready. He asks me if I’m here a lot. He asks me where I’m from. He asks if I’m OK. He asked me again where I’m from. He asks if I’m OK, again. He asks, again, if I’m in here a lot. I’m sure he means well. But, of course, this line of questioning disrupts my writing. And, yes, admittedly—from his perspective—it must be strange to see a person writing alone at a bar on a Saturday night.

Here’s what I imagined for this essay. I sit at the Joyland Bowling Alley Bar. On the wall, behind the bar, hangs a menu, like the kind you see in little league concession stands—white plastic, with black pressed-on letters: Pizza. Chili Dog. Pretzel. Bud Light Bottles. Bud Light Pitchers. The bar would be wooden—perhaps a remnant passed down from the Joyland Park Dance Hall. It would be dark and it would be earlier in the afternoon. The clash of pins knocking against wood rings out. Some nondescript nineties R&B song would play—maybe “Waterfalls,” by TLC, or “This is How We Do It,” by Montell Jordan, or “Shoop,” by Salt ‘n’ Pepa. The kind of songs you’d hear at a roller skating rink in the early nineties.

The bartender would be a girl in her early twenties, pretty with straight brown hair. A little rough around the edges. She’d wear old black high top tennis shoes. She’d have uneven teeth. She’d be slow to smile, unconfident and self conscious because of her teeth. She’d needed braces as a kid but never got them. I’d be charmed by her teeth and her lack of confidence. She’d have grown up in the neighborhood. I’d ask her about the place back when it was Joyland Park. She’d say she heard there was a rollercoaster. But that’s about all she knows.

Or maybe the bartender would be a thin man with gray hair—balding with a ponytail. He’d be wearing an Ozzy Osbourne concert T-shirt from the 83’ Bark at the Moon tour. He’d remind me of my old friend Jon Volz. Who used to be homeless. Who I visited at the mental hospital. Who disappeared. He’d know a bit about how a lot of the jazz bands played here. Charlie Parker, he’d heard. Which I would not think was true.

I’d drink at a cold Bud Light bottle and write on this same notebook page. My black ink pen would scrape along the paper surface. I’d imagine my grandfather—a musician, singer, and jazz piano player—seeng Stan Kenton here. He told me how he’d met Stan on the elevator after the show. And my grandfather made some cool nonchalant comment and Stan had laughed and played along. They were both probably drunk or well on their way. And Kenton had been his hero. And he’d met him after he played here at this once magical place called Joyland. He’d probably been smoking a filterless Camel cigarette. He’d smoked them since he was twelve—back when he was just a kid in eastern Kentucky. And I would think about such an important moment in a man’s life. And what a special place this had once been. All the big jazz bands had played here in the fifties—and how quickly that had all been forgotten. Even the bands themselves had been forgotten. I’d sit in the mostly empty bowling alley bar on a Saturday afternoon in mid-November and I’d think about that. I’d look for traces of what the place had been. Some leftover magic, maybe. The thought would have probably depressed me. I’d drink several beers fast to feel better. Then I’d smoke a lonely cigarette in the parking lot—perhaps looking out on a trash bin. Perhaps there’d be a stray gray cat beside the blue metal trash bin, licking its front foot as the sky light started to go. I’d smoke a Camel and think of my grandfather here meeting his hero, Stan Kenton. I’d start to feel low about the dusk, the light going, the way things always changed for the sadder. I’d probably sigh and think about driving home.

It got to where I couldn’t write anymore at the Mexican bar. I made my way through three Modelo bottles after the Michelada. I settle up. I walk out the rear entrance to have a smoke before driving home.

I stand under the awning and light my cigarette. Across the parking lot, in the window of a large low-rent apartment building, yellow lights on a Christmas tree flash on and off. The overhead light in the awning above me flickers, a lady walks across the lot and pushes the key into the lock of her silver, dented up Honda Accord. She burps. Her engine grinds, attempting to start with much difficulty, and finally turns. I hear a plane go overhead. I hear cars going down Versailles Road—behind me. I flick my cigarette onto the ground and wait for it to stop glowing orange. I look out at the big metal transformers on the two utility poles across the parking lot. I hear an HVAC unit kick on. It starts to feel colder out. My ears and fingers feel the cold. I see a man smoking by the front door of the restaurant.

I sit in my car. On the other side of Versailles Road, the signs light up: McDonald’s—red and gold; Taco Bell—purple and yellow; Cash Tyme—green. A Grateful Dead song from a May 4th 1977 bootleg starts playing on my car stereo. I’m not in the mood for music. I turn on the audio book I’ve been listening to—The Book of Laughter and Forgetting by Milan Kundera—and back out of the parking space.

I’ve written these last few pages at my kitchen table on a Thursday afternoon in late November. I’m playing hooky from work. I hear the pen scraping the page and darting down to make contact. I smell the ink. I write with my long favorite pen—Zebra F-301. I started using them back when I worked in advertising sales. They’re simple stainless steel, well-made, but nothing fancy. They are plain. I’m writing on a black notepad called “Rhodia” I found at my favorite bookstore in Louisville. It’s a long page—perfect for writing. As I’ve written these last pages I watch outside my kitchen window in the country. The sky is gray—with one layer of clouds covering. A few brown leaves hang onto the apple and maple trees. (As I’m line-editing this essay a month later—on Christmas Eve Day, no leaves remain.) The limbs and leaves sway. Back and forth. The cedar and spruce move in small sways. A red cardinal sits on a thin branch on the center apple tree, then leaves. I hear a train whistle blow from the east. A groundhog—the color of faded fence boards and winter tree branch—gathers things on the grass with his paws. A calico cat jumps on the table from time to time and sits beside this notebook, looking at me with her big green eyes. I hear a plane go over. A neighbor calls to his dog. The groundhog scurries back under the shed. I feel good to be in November.

My grandfather’s brother, Harold, and I drove down to Menifee County in eastern Kentucky a month ago. He drove and his cairn terrier, Trace, rode in the back. He showed me where the family came from, told me stories, and we went to the family cemetery. The cemetery was off a rural road, which you first take another couple rural roads to get to. The cemetery was on top of a hill. A great cedar tree stood in the cemetery’s center, on the hillpeak. A burnt black stretch of bark showed at its center. The cedar tree had been struck by lightning. The trunk of the cedar was broad. Maybe the largest cedar I’d seen. I rested my hand on the burnt mark in its trunk. My hand smelled of cedar. The cedar’s pines and upper branches were healthy to varying degrees. Some limbs were in excellent condition, full, green, lively. Others showed sparse and bare wood instead of full dark green. I imagined how the nutrients from the decomposing bodies of my ancestors had nourished the roots and trunk, and limbs, and pine needles of this tree as it grew. Just as their cells and genes have nourished me. Me, this great lightning-struck cedar, and my great uncle are all related.

On the way back, we stopped and had dinner at a steakhouse in Lexington. We sat at a bar booth. The room was all dark wood walls like a wealthy captain’s quarters. We started with Old Fashioneds, which were not well made. Then I had a beer. My great uncle ordered a bottle of red wine, and we shared it. It was good wine. Smooth, not tart.

My great uncle told old family stories. I asked him about my grandfather, who died last year. His stories about his brother and my grandfather—Don Mann—had a different spin than the ones I’d heard. Some were more innocent (Harold was the youngest brother) and some filled in gaps of his life I’d never known. I never knew my grandfather had been a bartender in Lexington for years, living with his brother, while he struggled to pay child support to my Nanny and my mom and aunt and uncle.

I tell Harold I’m writing an essay about Joyland.

He takes a drink of red wine.

He tells me his high school took a field trip from Menifee County to Joyland Park one spring. That was the first time he saw it. They swam and rode roller coasters all day. I ask if people made a day of it—swimming and riding coasters in the day and staying for the Joyland Dance Hall bands at night. He said it didn’t work like that. It was separate. He says he remembers years after the field trip, he took a girl named Kathy to the dance hall one Saturday night. He walked outside the dance hall to have a cigarette. In that moment, smoking a cigarette outside the Joyland Dance Hall, jazz band playing in the background, people streaming by—alone in the crowd to think—he made a decision. He realized he didn’t want to bring Kathy to the dance hall. Or any other girl. He decided from that moment on to just be himself. And stop hiding things about himself. He kept that promise to himself. That promise he made outside the dance hall at Joyland on a late fall night.

But how many people have the courage to be themselves?

And how many people are fully themselves?

And how many people meet their heroes?

And how many people meet their heroes and make them laugh?

So, maybe, all I know of Joyland, really, is that my grandfather met his hero there, and his brother changed his life there. And, yes, the bowling alley that carried on the name is gone—and so a sad misplaced monument for people like me is missing. But there must not be too many people that think like me.