Contemporary pop culture’s representation of sex workers has undergone a remarkable evolution from moralistic cautionary tales to neoliberal success narratives. In her book Sex Work in Popular Culture, Lauren Kirshner analyzes over 100 pieces of media ranging from blockbuster films to indie documentaries while—refreshingly—consulting the true experts: sex workers themselves. Whereas the screen once confined these characters to death or marriage—a classic case of Hollywood’s “damned if you do, dead if you don’t” approach to female sexuality—today’s portrayals increasingly depict sex work as legitimate labor performed by entrepreneurs who wield their “erotic capital” in pursuit of economic mobility. This shift coincides with growing activism for sex workers’ rights and the decriminalization of sex work. Decriminalization frameworks seek to remove criminal penalties for sex work while maintaining laws against trafficking and exploitation, allowing sex workers to operate legally and access health services and legal protections. In congruence with this, popular media is becoming an important cultural forum in which feminist debates about bodily autonomy, labor rights, and exploitation play out decorated in sequins and stilettos. However, Kirshner asserts that these seemingly progressive narratives often transform sex workers into “neoliberalism’s ideal subjects: ‘entrepreneurs’ and flexible precarious service workers who are young, conventionally attractive, individualistic and apolitical,” replacing the vital work of collective organizing with individualistic hustle culture. Instead of amplifying sex workers’ actual struggles for legal rights, workplace protections, and the structural changes needed to address the poverty and inequality that drive many into the industry out of necessity rather than choice, these narratives offer sanitized stories of personal triumph within capitalism’s existing framework—essentially trading the Madonna-whore complex for a hustler-victim binary that’s equally reductive in its own glossy, Instagram-filter way. While decidedly more nuanced than their stereotypical predecessors, contemporary portrayals like Hustlers celebrate characters who beat the system on its own terms rather than challenging the structures that necessitate sex work in the first place—suggesting the ideological limitations of Hollywood’s newfound respect for sex workers.

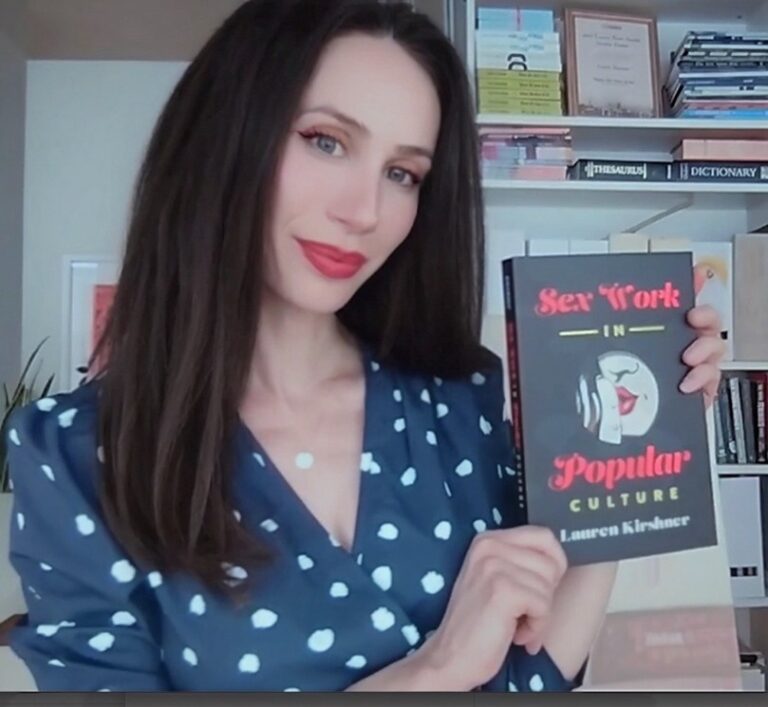

KS: Your new book Sex Work in Popular Culture, tackles a complex and evolving subject matter. What drew you to studying sex work representation in popular culture?

LK: Sex workers were everywhere in the movies, talk shows, and TV I grew up with, but their stories mostly followed predictable arcs—death, marriage, redemption. Whether punished or saved, they always ended up as tawdry thrills or cautionary tale chalk outlines, rarely reflecting the realities of sex work from the perspective of women who chose it as a profession.

But around the turn of the aughts, I started noticing a shift. Sex workers were increasingly framed as workers in portrayals that challenged stigma, showing them as full people rather than tropes. I wanted to explore these new narratives—particularly in the last two decades—to understand how they reflect broader cultural shifts and shape how we think about labour, sex, bodily autonomy, and power.

KS: Your book highlights the long history of sex work representation in Hollywood. How have these portrayals evolved over time?

LK: Since the early 20th century, Hollywood has told over 1,400 stories about sex worker leads—more women have won Oscars for playing them than for any other role—yet real life sex workers are still criminalized and stigmatized. Pop culture has long been fascinated by sex workers, but through a moralizing, voyeuristic lens. In crime dramas and talk shows, they were either tragic figures or hypersexualized props.

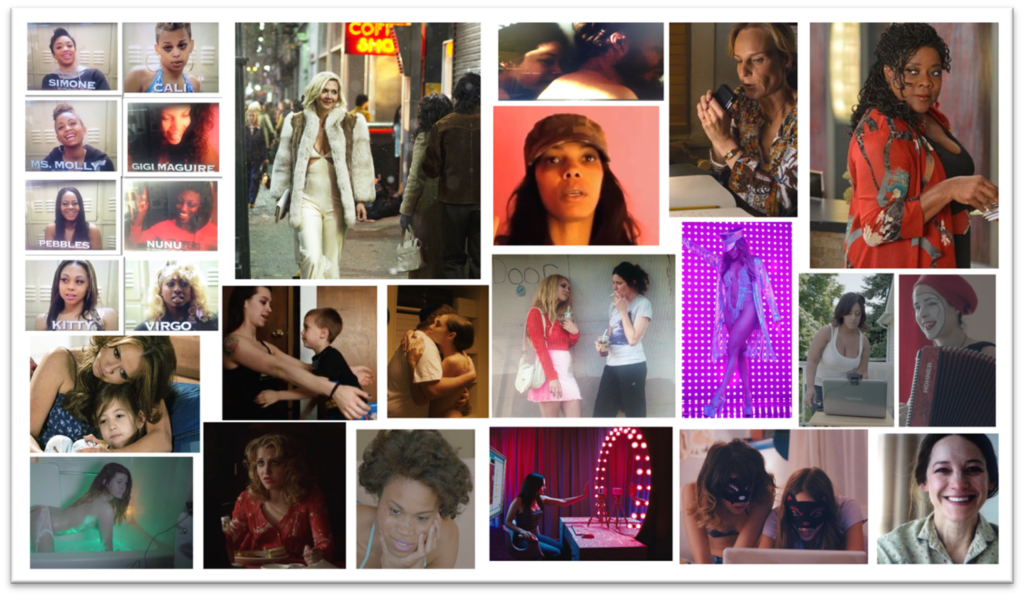

In my book, I explore a new wave of sex worker portrayals that frame sex work through a labour lens. What stood out to me was how many of these stories highlight the struggles sex workers share with gig workers—uncertainty, branding, and economic survival—while showing the diversity of sex workers including mothers, students, and women of all ages and motivations. Films like Hustlers depict sex work as a strategic hustle, while documentaries like Cam Girlz and Candice explored erotic labour as creative performance. The Sessions framed sex work as care work. Most recently, the Oscar-nominated Anora tells a love story that flips Pretty Woman on its head. Pop culture is also showing the issues shaping sex workers’ everyday safety, from stigma to policing.

That said, pop culture still has its limits. Some portrayals glorify top earners while ignoring financial instability, criminalization, and racial disparities. Others push “girlboss” narratives,” selling empowerment as personal success while sidestepping larger issues like rights and criminalization.

KS: Why did you feel this was the crucial moment to publish this analysis?

LK: Feminist scholar Gayle Rubin wrote that “there are particular times when sex is re-negotiated” and today is one of them. Media coverage is becoming more nuanced and sex worker activism is gaining ground—through unionizing efforts, political campaigns, media projects like Get Your Booty to the Polls, and writing. In 2021, 42% of registered voters supported decriminalization.

For decades, media studies has mostly focused on films that framed sex work through violence or oppression—partly because these were the dominant narratives, but also because scholarship traditionally viewed sex work as exploitation rather than labour. While valuable, this perspective left a gap in understanding sex work as work.

My book fills that gap by analyzing how contemporary media reflects shifting economic realities—wage stagnation, gig work, and precarity—through the lens of sex work. As precarious labour becomes the norm, pop culture’s portrayals of sex workers echo broader anxieties about survival in a shifting economy where everyone has to hustle.

KS: Could you walk us through how these initial research interests evolved into this book?

LK: Two moments sparked this book. First, watching The Sessions, which framed sex surrogacy as professional care work—an approach I’d rarely seen. Then, while researching historical images of sex work in an archive, I was struck by how often labour was erased.

A few images stand out. A 1915 San Francisco Warning! sign, a relic of white slavery panic, warned women about procurers. A “Rescue House for Prostitutes” photo showed ex-sex workers bent over sewing machines, “reformed” but relegated to low-wage labour. Hogarth’s “A Harlot’s Progress” mapped a woman’s descent—lured into sex work, then imprisoned, then dying in squalor. Across visual culture, sex work was rarely depicted as labour.

Early film reinforced this pattern, presenting sex work as morality, spectacle, or tragedy. This realization led me to sex worker activist creators like Carol Leigh, Candida Royalle, Margot St. James, and Melissa Gira Grant, whose work re-framed sex work as skilled, strategic, and shaped by economic forces. Their perspectives, along with interviews with sex workers on pop culture’s portrayals, shaped my book. Insights from those interviews open each chapter, grounding it in lived realities.

Each chapter explores a different profession—erotic dancing, webcam modeling, escorting, sex surrogacy, and porn—analyzing these portrayals through the lens of entrepreneurism and emotional, aesthetic, display, and care work.

KS: Your book examines sex work within the broader context of contemporary feminist discourse and capitalist structures. How do you see the relationship between mainstream feminism’s historical neglect of sex workers’ voices and the current moment?

LK: While sex work has always been a labour issue—sex workers organized in 15th-century France, and Emma Goldman defended them at the turn of the 20th century—mainstream feminism largely treated them as victims. By the late 20th century, feminist split into three camps: the oppression (sex work as exploitation), sex-positive (sex work as agency), and labour (sex work as work). Despite growing support for decriminalization, anti-sex work feminism continued to erase sex workers’ voices.

But sex workers fought back. In 1972, Margo St. James founded COYOTE, the first U.S. sex worker rights organization. Carol Leigh later coined the term “sex work” to reject victimhood narratives. Their activism laid the groundwork for today’s movement, where sex workers are demanding rights, not rescue.

This shift is reshaping pop culture. The Deuce and Hustlers consulted sex workers for accuracy, former sex workers like Isa Mazzei (Cam) and performers like Mya Taylor (Tangerine) bring authenticity to the screen. A few decades ago, feminism framed sex workers as victims. Today, they’re shaping its future.

KS: Your book arrives at a time of significant debate around sex work policies globally. How do you see popular culture’s portrayal of sex work influencing public policy discussions and vice versa?

LK: Pop culture and public policy don’t exist in silos—media shapes how sex work is understood, influencing institutions, lawmakers, and public perception. While major organizations like The Lancet, WHO, and Amnesty International support decriminalization, criminalization frameworks still dominate. Pop culture gives vivid shape to these policies, weaving them into compelling stories that expose their real-life effects.

For example, HBO’s epic The Deuce illustrates how criminalization forces sex workers into more dangerous conditions—working in isolation to avoid police at their own peril. This mirrors real-world policies that push sex work underground, increasing exploitation and violence.

Media coverage can also drive real-world action. Studies show that sex worker murders receive less media coverage and are less likely to be solved. Netflix’s The Ripper highlighted this stigma, leading to long-overdue apologies. Similarly, Lost Girls kept focus on the sex worker victims of the Gilgo Beach killer, renewing public pressure and leading to the 2024 arrest of the suspect. These cases show how media scrutiny can force institutions to act.

KS: With Sex Work in Popular Culture now published, how do you hope it will contribute to both scholarly and wider discussions?

LK: I hope my book contributes to the shifting conversation around sex work—from a moral debate to an issue shaped by economic and social forces—placing it within broader discussions of labour, gender, and capitalism. At its core, this book is about how we tell stories about work, survival, and power. Hustlers captures this shift perfectly, portraying erotic dancing as gig work and critiquing inequality. As Jennifer Lopez’s character, Ramona, puts it: “This whole city is a strip club. You got people throwin’ the money and people doin’ the dance.” But these portrayals go beyond fiction—they shape how we think about work, precarity, dignity, and rights. Since most people’s understanding of sex work comes from pop culture, what we see on screen matters.

Recently featured in CBC and in Jacobin.