After a penance of one thousand years, Bhagirath, the great-great-grandson of King Sagar, coaxed a goddess to leap down from the heavens to earth. Her name was Ganga, an indomitable river. Fearing destruction, as her force was infinite, Lord Shiva entrapped the goddess in his tangled tresses.

Until, Bhagirath begged the Lord to make her free.

From the Gangotri glacier to the Bay of Bengal- 2500 kilometers- the goddess flowed, giving birth to the old cities of India: Varanasi, Mathura, Prayagraj, Kannauj, Agra; often devouring her children in rain. Until near Giria- a nondescript Bengal village- she became two.

Two new rivers were born, two new names, following two separate paths. One travelled to the south. The other travelled east, and then to the south again, to meet the same sea, the Bay of Bengal, at a distance of 300 kilometers from each other. In two separate countries: India and Bangladesh.

The river that travelled to Bangladesh is called the Padma. The river that stayed in India is called the Hooghly.

Calcutta- the capital of West Bengal, an eastern state of India- is by the river Hooghly. Where Job Charnock, a British East India Company agent, established a factory in 1687. The factory – in time – became a trade base, then a garrison, a fort, a city, became the capital of India. Until 1931, when India’s capital was shifted to Delhi, Calcutta fell back to be the capital of the province of Bengal.

The province of Bengal was separated into two in 1947, after India’s independence. The eastern part became East Pakistan, after a new country named Pakistan was formed partitioning Bengal and Punjab. The western part remained with the old country as one of its 14 states and was named West Bengal, indicating an eastern part that was missing. In 1971, East Pakistan, after an armed struggle and with India’s military assistance, became an independent country. It was named Bangladesh.

West Bengal, the neighbouring state- speaking the same language and worshipping the same literary heroes- has continued to be an Indian state.

I studied in West Bengal. At the higher secondary in Howrah – the twin city of Calcutta – in a residential college founded by the Ramakrishna Mission. The river Hooghly separating the two cities: Howrah and Calcutta. The two famous bridges: the Howrah Bridge and the Bally Bridge (the Howrah Bridge a motorway, and the Bally Bridge is both a motorway and railway) were the connectors of the two cities.

My college was on Hooghly’s right bank, beside the Belur Math, the headquarters of the Ramakrishna Mission.

Where my maternal uncle – a Dr. Das – a PhD in Applied Mathematics from Indian Institute of Technology would come to visit. A researcher at the Indian Statistical Institute; it was for him only a bus journey from his laboratory to my college. The Indian Statistical Institute was on the other side of the river, at Baranagar, in Calcutta.

He would travel by a ramshackle bus- a vibrating iron and aluminum cage with a floor of wood- to cross the Bally Bridge sitting on a thinly padded chair, beside a pull up and down window. The bus would pick him up at the Dunlop stop on Sundays and drop him at the Belur Math minibus station. From where, a stroll of a kilometer would bring him to the college gate. After getting the gatekeeper’s permission, he would walk a few hundred meters more to meet me at the hostel.

We would spend the afternoon, on those days, looking at the river from the right bank. Our legs dangling a foot above water.

We would speak in a soft voice so as not to wake up the meditating monks in the nearby temples, so as not to startle the scavenging crows on the grass, till the evening prayer bell in my college rang. I would inform him of my academic progress, as the uncle was the most educated person in the family.

The conversation would veer towards calculus, the concept of limit; what it means to near an integer but never to reach it. Piskunov’s Soviet calculus book. How mathematical research could be a career in America. Watching at the same time the muddy mass, the temporary islands created by the rotten straws, plastic and an occasional porpoise.

Until the uncle, whose professional life I wished to emulate, would quiz me on the Bernoulli’s principle, would tell me that the Bengal ground water was turning saline, becoming arsenic prone. The shallow pumps of rural Bengal were sucking the potable groundwater dry.

There would be sadness in his voice; his eyes would be stiff with defeat when he would inform me that the Hooghly was to be dredged again so that the ships could enter the port. With the dredging department so inept and the water bureaucrats so oblivious, he bore no hope. His fear was that Calcutta would share the fate of Tamluk; a town 85 kilometers down south, where there had been a busy port in 375 AD, now dry.

Then one Saturday – when he was travelling to a scientific conference, when I knew that he would not come to visit me the next day – I put in a request to our warden, a saffron monk, to give us permission to bathe in the river. The monk was hesitant.

Even though it is a pious act to bathe in the Hooghly as it is a part of goddess Ganga. On the other hand, he was responsible for our well-being. There was a rumour that some students had stolen a bottle of alcohol from the chemistry laboratory and drank it, mixing it with tap water. They were alive, but their erratic behaviours were heard for two nights. It was in his reputation not to indulge us even more. ‘I would allow you’ – he said – ‘but only if you know swimming.’ Six of my classmates and I cried in unison, boasting about our rural upbringing, claiming to have swum in even more treacherous waters.

‘I have swum in the Kansai’, I said, ‘from this side to that side’, pointing at an imaginary place that was beyond the hostel wall, beyond the cigarette shops on the road. The warden tried to follow my direction and failed. The truth is, in Kansai, I swam in two feet of water, holding a river boulder for my dear life, under my mother’s watchful supervision.

He hesitantly granted permission.

The next day, after the morning study hour, we marched bare-chested. In a pair of cotton shorts and blue-white chappals; a green cotton towel wrapped around our heads. Towards the gate of Belur Math without supervision. In another invasion to adulthood, we lied to the guard that ours was a prayer visit. This unusual attire was a social service uniform.

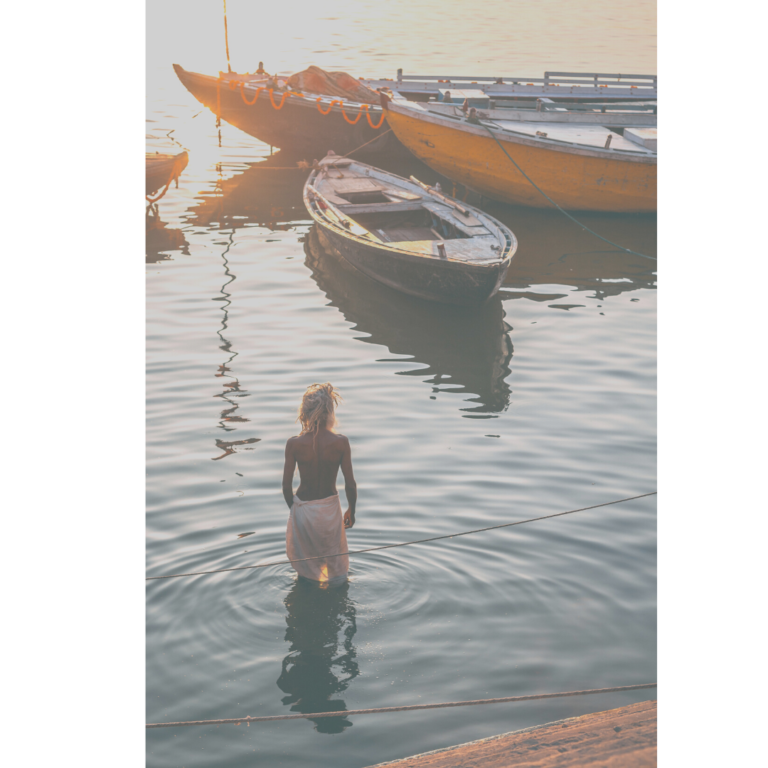

Once inside, quickly we ran to the one of the bathing ghats of the Math. Before anyone caught us, we were at the water.

A scorching summer sun was shining overhead, small beads of sweat on our chests; an unexpected coldness gripped my ankles when I was in the water. Looking at the river a fear came. The possibility of drowning had become apparent. An encounter with a demonic force that rose from the river’s belly, it’s more-than-a-kilometer breadth, its gushing waves. Then a thrill came over me to subside all my fears – a sudden hubris – making me feel for a moment invincible.

*

When Bhagirath was the king of Ajodhya, his kingdom came under the scepter of severe famine. Bad years haunt every ruler. Bhagirath’s misfortune was chronic. Upon the ministers’ advice, on a pilgrimage, the young king came to know of a curse that had befallen upon him unknowingly. His great grand uncles- sixty thousand warrior princes- had been burned alive at a distant land, in a military campaign.

Their souls were still trapped in this mortal world.

The military campaign itself had been an extraordinary ritual. A king seeking domination over neighbouring kingdoms would set a horse free so it could roam the world. The king’s army would follow the horse. Wherever it went, the lord of the visited land would either pay a tribute or wage a war against the king. The ritual would last a year, when after conquering a large swath of land the army would return to the capital, along with the tired horse. The horse would be sacrificed to the fire-god- a reward to its aimless wandering. Its burnt meat would be devoured by the king.

After showing such domination, a king would be hailed as a Chakravarti or king of the kings.

Sagar, the great-great-grandfather of Bhagirath, was one such ambitious king. By the might of his sixty thousand warrior sons, he wished to lay claim to the earth. He set free a sacrificial horse. Which was soon lost. The pursuing sons, eager to find the horse, marched and marched till they reach the circumference of India, to the abode of a sage named Kapil Muni, a Samkhya philosopher, believed to be a reincarnation of Lord Vishnu.

Kapil Muni’s abode was an unknown place – far away from the capital Ajodhya – in an island in the Bay of Bengal. Where the landmass of India sinks into the sea and the sea takes over. Now named after the king, Sagar Island, it is the largest island of the Sundarban delta. The Sundarban delta being the largest river delta region in the world.

It was the king of the heavens, Lord Indra’s mischief- having grown weary of King Sagar’s ambition- as a king accrues virtue with every military campaign and sufficient virtue accrues him a right to rule the heavens in his afterlife. To dent Sagar’s ledger of virtue, Lord Indra took it upon himself to steal the horse, tie it to a tree near the hut of Kapil Muni, counting on the Muni’s furious temper.

The Muni was amid a terrible penance. Hearing the commotion, he opened his eyes. To find himself surrounded by sixty thousand warmongering princes, who without knowing him or his penance, had cast insults.

He looked at them in a fury. A column of fire, emerging from his eyes, caught the princes, engulfing and burning their royal bodies into cinders. The ashes of their bones were laid on the ground, without a proper ritual bestowed to the dead. Their souls, reaching neither heaven nor hell, were trapped in the mortal world. Such an obstructed journey to the afterlife bringing misery to the descendant, Bhagirath, the present king.

*

My relatives who went to Sagar Island on a pilgrimage – where the second largest religious fair of India is held every year – brought back several picture postcards as a gift from the fair.

The four-colour offset printing was not affordable then. Block printing and letterpress were the norms. A drawing in a single colour beside black was rare, made by mixing pigments and then dousing a wooden block with the mix and stamping it on a piece of paper: making every picture full of dots and grains.

In one of those grainy postcards, Kapil Muni was depicted.

At the center of the postcard, he was looking fiercely at King Sagar’s finger wielding sons- fire coming out his eyes to grab the unsuspecting young men. To his left, Lord Indra- thief like- tying a horse to a tree. A white temple was laid above: Kapil Muni’s ashram, a temple one can visit if one travels to the island.

At the top right was Bhagirath – the great-great-grandson of King Sagar – a thin, tenacious man, standing on one leg, donning a hair bun, two hands folded above the head, praying to Lord Brahma for one thousand years. Below, there he was, again. Now on two legs. Still thin and still obedient, bent forward with two folded hands in front of Lord Shiva begging him to restrain the goddess and then to free her.

*

From where the seven foolish boys who had lined up to jump into the water of the Hooghly, in a Sunday misadventure; from the bathing ghat of Belur Math to the muddy mass of cold water; there, on the stone pulpit, the glimpses of the past didn’t visit me as they do now. I was young, restless- lacking the tenacity to join impossible dots. The ability came to me later. With time. After collecting a thousand brickbats. When I taught myself to avoid responsibility. When I taught myself to be oblivious to the opinions of others.

It was I who jumped into the water before the other six boys. It was I who first gulped the water. An unwilling somersault later, that ended abruptly hitting the surface of the river, it was I who was drowned immediately under the river’s monstrous gush. My body was nudged to a half-turn, as the river aligned me to its direction. Before knowing how much trouble I was in, I was floated away from the bathing ghat.

Between the squints, the right bank was passing me by, with the speed of a mail train. The men on the bank were gesticulating. Their voices came to me sporadically, muffled.

It was a dream.

“Ho-ld … on’, someone was shouting, ‘Ho-ld … on.”

I was thinking, “What hold on? That I can’t.’

‘I am now one with the river.”

It is hard to describe what I felt then. I am well now, at home and safe. On my writing desk, there is a half filled coffee cup and a pile of invoices. A warm LED lamp is glowing overhead. Here, there is no shadow of danger looming.

It was as if I had woken up from sleep- suddenly aware of my existence. Someone inside me was screaming. I had to ignore his voice. My mind- after scaling a peak of alertness- was numbing. There was no more deliberation. Any attempt at concentration was failing under the weight of anxiety. A sense of surrender had taken over as it had dawned upon me that a monstrous force had taken hold of my body. It was so uncaring, so neutral that it didn’t matter what would happen to me next.

Uncaring, but … consistent. The thought came to me as hope. A natural force within its everyday parameters is consistent. That is why eight billion people hope to live on, not drop dead under the conspiracy of the gravitational constant. Minutes had passed, my nose was still above water, I was alive. Proof enough that something had favoured me.

I remember, once my uncle had told me, pointing at a whirlwind in the river, “Look, a turbulence. The most complex physical phenomenon in the world. Impossible to model.”

“Not even with the help of a CRAY?” I asked, showing off my knowledge about the American supercomputers.

He said, “Not even with the help of a CRAY”.

Between hope and hopelessness, I did not have the time to ask myself then; so I ask myself now: was I part of turbulence? Perhaps not. Had water and I behaved? As per Archimedes? As per Bernoulli?

From somewhere, a tree log had appeared and was passing me by. No, not a tree log, not a plastic board, nor a litter-mound. A rectangular shaped flotilla – perhaps the skeleton of an idol- without mud – the rotten straw and the bare bones of bamboos- after immersion. It was dancing with the wave and rushing me past. I threw myself at it and grabbed the shape with both of my hands. It was caught. A blotted, slimy cloth bag that drowned immediately under the weight of my body. When it floated up, it came with a pair of shoulders and an unfinished neck. A disheveled head must be somewhere in the water. A stench came to fill my nostrils.

A dead body. I was swimming with a dead body. My hands were grabbing its bloated trunk. My fingers were piercing its flesh.

*

Now that I had something to hold on, I was floating. I could look around to make up my mind. The river, without resistance, was pulling me even faster. I tilted my head towards the bank and began to kick vigorously. Not to resist the pull of the river, but to give a direction to the both of our bodies, making my legs work as radar.

It was an arduous process. The change of direction happened slowly, inch by inch, after an immense struggle.

There was no bathing ghat to be found nearby to anchor myself, to get myself to the safety of the ground. When courage was depleting; near Ghusuri, a large ferry ghat appeared. The water became shallow and before I knew it, I could stand. Leaving the body aside, I swam towards the bathing steps. The body, after leaving me, got trapped against the bamboo ramp of the ferry. I stumbled and stumbled on the river mud to reach the steps, trembling under the weight of my exhaustion. I noticed that the legs of the body were tied with a blue nylon rope.

Without thinking about it, I rose up; climbing up the steps of the bathing ghat of Ghusuri like revived sons of King Sagar – to the relative safety of the land.

As a child, I would ask my grandmother to tell a story everyday, and she would unearth from her memory stories from the epics and the Puranas. She had told me that even though Ganga was an all-knowing goddess, the geography of India was unknown to her. It was Bhagirath who had shown her the way, while blowing a conch. The goddess followed his conch-signal without a fuss.

Reaching Kapil Muni’s hut, Bhagirath held a shraddha ceremony, sprinkling the ashes with the Ganga water, to let his great uncles be free from the mortal world.

*

My parents never knew that I was about to die. It took a week’s pleading to the warden, to the principal – I ran like a spindle with folded hands – to coax them to not call father. It was punishment enough that I had had a brush with death. The Board examination was in the offing; after that I was not the Mission’s concern.

In the meantime – I promised them – that I would not repeat my feat.

My parents were better off not knowing. It would have been another irksome, tiresome episode. In their long obsession to improve me- academic achievements and physical well being- in the throes of terrible anger, a few times, they have wished me dead.

The burden of bringing up a stubborn child is much.

My death might have been a respite to them. Or a regret.

One can never tell.

A constant struggle with a pig-headed boy whose fate is entwined with theirs. A boy who dwells in his own realm and nobody else’s- and how his misery has become their own- the never-ending helldom that is parenthood.

How they have been burning since my conception, since their marriage, and burning me with caustic words on desolate days; issuing violent, vulgar prohibitions meaning only to improve their first son.

I too have returned the favour. With bitter words and with cold indifference. Nursing dreams of inflicting sporadic violence.

To call this essay about a river is a sham. The essay is not about me either.

Is it about good luck?

I studied probability during my Bachelor of Science days – although not diligently. Skipping the Kolmogorov’s book, I read the portions of the War and Peace in which Tolstoy wrote long passages on chance.

Unlike him, I am not a believer. Unlike him, I don’t believe Nature is benevolent.

Yet in that cynical disbelief, a mighty river appears. A fierce stream joining the dots of my childhood, my boyhood, my adulthood. The stories that I heard from my grandmother, my uncle— the unforgettable epics, the Puranas — the grand tales of eighteenth century European scientists — Newton and Bernoulli. They mix to make muddy water and it flows.

And I float on it.

I ask myself: From where had the bloated body come? Who had sent it? Who had tied the man’s legs? Was he too the dead man’s first son?

How tenacious was Bhagirath! One thousand years of penance. To serve his subjects. To free his ancestors.

Being a commoner, I do not have his virtues. I am barely afloat. Crumbling under uncertain memories, I can not tell where it is land and where it is water.