I meet Andrea Benoit on Balzac’s patio, in the center of Ryerson’s campus. The construction booms around us as students traverse Gould Street, still cresting on the high of a new school semester, the bustle softened by morning sunlight. Andrea is alert and bright, nibbling on a blueberry scone and chatting animatedly about her latest labour of love.

Her new book, VIVA MᐧAᐧC: AIDS, Fashion, and the Philanthropic Practices of MᐧAᐧC Cosmetics (University of Toronto Press, 2019), explores the extraordinary, yet the curiously uncharted cultural history of MᐧAᐧC Cosmetics. MᐧAᐧC is now an iconic brand, with stores across the world, but Benoit takes us back to its origins in 1980s Toronto. The company was founded by Frank Toskan and Frank Angelo, life partners and business owners lovingly known as “the Franks.” MᐧAᐧC immediately set itself apart as a company that refused to play by the industry’s established rules; giving free creative reign to their trusted counter staff, encouraging customers to mix and match their own colour palettes, developing unique matte colours specifically for darker skin tones, and even refusing to advertise their own product for 10 years.

Benoit’s text focuses specifically on MᐧAᐧC’s groundbreaking 1994 AIDS campaign. “At a time when associating with AIDS was considered a very risky move for a brand or corporation, MᐧAᐧC assumed a defiant stance,” writes Benoit. The company introduced VIVA Glam, a fundraising lipstick in a brilliant matte red. As a move of corporate philanthropy, their campaign remains largely unmatched; one hundred percent of the lipstick sales went (and continue to go) directly to the MᐧAᐧC AIDS Fund. MᐧAᐧC’s first official advertisement—a risqué poster featuring the celebrity drag queen RuPaul in a red bustier and boots—broke the silence on AIDS during the mid-90s, finally voicing the anguish and injustice felt by those in the city’s devastated fashion industry. Benoit examines MᐧAᐧC’s campaign as one of the few positive cases of cause marketing, combining her previous scholarship on corporate philanthropy with first-hand accounts and archival research to create a conscientious text which finally colours in the outlines of the successful Canadian brand.

The White Wall Review was thrilled to have the opportunity to talk with Andrea about her research, the personal connections she’s formed, and whether or not capitalism can ever allow for real social change.

What drew you to writing about MᐧAᐧC in particular?

Writing about MᐧAᐧC actually came out of my graduate work in ComCult (Communication and Culture) here at Ryerson, where I was looking at cause marketing and the intersection of the commodification of social causes with identity issues and representations of diversity and inclusion. Specifically, my work was on the Dove Campaign for Real Beauty. At the time, that was still a pretty new campaign, and nobody had really written anything about it. Like any project, you need to have a future direction, and mine was essentially looking at how cause marketing works in other types of well-known campaigns like Product (Red), MᐧAᐧC, and breast cancer culture. So it was really part of a larger idea. And when I started to investigate MᐧAᐧC, I realized there was absolutely no critical scholarship on their brand, so it was the perfect doctoral project.

Yes, in your prologue you point out the lack of biographical work published on MᐧAᐧC—why do you think their story has been overlooked?

My guess is partly that nobody knows exactly what to do with it; it doesn’t fit into any of the bodies of critical scholarship that exist. I was so surprised to see that even big compendiums of the history of beauty culture and cosmetics companies really only had a footnote on MᐧAᐧC, here and there. I really don’t know why—it’s mystifying to me. There’s a lot of popular press on MᐧAᐧC, and I did a lot of research to try and find those newspaper and magazine articles and things like that, but they all pretty much tell the same story again and again. So what I needed to do was go beyond that.

Were you familiar with MᐧAᐧC as a makeup brand beforehand?

Totally! I was definitely an 80s Toronto girl. I’m very much one of those people that I talk about in the prologue, having MᐧAᐧC lipstick in my pocket, going here and there, and going to their counter at The Bay—I was absolutely one of those people.

A lot of primary research went into writing this book, including sifting through archives at the ArQuives and York University. Can you talk a bit about that collection process? Did you experience any challenges?

Well, you know archival research is only as good as what people keep around. And what I found most useful in the end was probably the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, which is now renamed the ArQuives, just up the street. They had the best collection of Fashion Cares and D.Q. (a Drag Queen show fundraiser for Casey House) materials, and everything AIDS-related. They had tons and tons of it! The problem is that it’s not very well organized there.

It’s entirely run by volunteers, and in some cases, volunteers who have worked there for decades. They directed me to a corner of the basement—there weren’t really any lights down there, and there were just boxes on shelves. It wasn’t organized, but they knew enough to send me to that corner. And I just went through boxes and found a whole bunch of things that were tangentially related to MᐧAᐧC. But that really helped fill out the context in which philanthropy around AIDS in this city took hold. In the end, though, you’re really reliant on what people think is valuable and what they don’t think is valuable.

And you also explored the York University archives?

Yeah! So interestingly—and this happened probably about a year before I finished [the Ph.D.]—York had received some VHS tapes of early Fashion Cares shows from the AIDS Committee of Toronto. And I guess it took a while to catalogue and organize them because one day they just came up on my searches. So I spent a lot of time at York in the library, and I got every videotape that they had. I went through every single one of them and wrote down everything I saw. In my book, I describe some of the D.Q. shows and I can do that because of the videos I found. Subsequently, there’s a Facebook group for D.Q. and some of those drag show clips are on there now, just done by people who are still alive and still remember. But that was a real find.

You were also able to speak to Frank Toskan, the co-founder of MᐧAᐧC; what was it like working with him?

He was amazing! It wouldn’t have been a project without him. I really wanted to meet him and talk to him and kind of have his blessing to continue with this project. But I had no way of knowing how much he would participate and how much he would help me. And, probably, he couldn’t have known either until we met and started working together. Our first meeting was only about an hour, and it was pretty limited. In many ways, he told me the same story that I found in all of the other newspaper and magazine articles—probably the same story that he’s told thousands of times. It was only when we finished and I said, “I really appreciate you taking this time…,” that he said, “Oh we’re not done yet, I’m not going to leave you like this!”

So he had me back [to his house] and I’ve been back half a dozen times in the last couple of years to do different things. We spent a lot of time with the initial interviews—I have about 16 hours of interviews in the gathering stage. I went back to confirm things, I went back to give him a draft (he read the very first draft), I went back to dig through his own boxes of memorabilia, and then I went back again to take them—he actually let me take them! Frank made all the difference; it wouldn’t have been what it is without his participation, but also his endorsement of the project. He said that he had been approached by scholars over the years but I had been the first one that he worked with [about MᐧAᐧC]. So somehow I convinced him that my motives were pure [laughs].

And you talked with several other people as well. How did you go about finding this network of MᐧAᐧC contributors?

It wasn’t easy [laughs]. So when I decided that I needed to do these interviews, I wasn’t really sure where to start. It would be impossible to just look Frank up on the internet and find his phone number. He’s very well protected. And as it turned out, that Fall of 2014, he was honoured by the Design Exchange. They named him their “person of the year,” so to speak, and they honoured him for his “creative activism” in their annual fundraising fashion design gala. So I bought a ticket, I went to it, and I basically followed him quite closely and made a move. I introduced myself and said, “I would like to interview you.” And he said “Yeah, sure, great! You should’ve just emailed me!” He made it sound so easy [laughs]. But when I emailed him, he didn’t reply.

So I cold emailed the president of the Design Exchange, who had organized the event. I said, “Look, this is what I am doing, I went to the event, I introduced myself to Frank, I’d really like to interview you as well about why you chose Frank and what the point of all of this was.” She agreed and I went to meet her, and when I started to ask her some questions, she said, “Actually I’m not completely comfortable answering these questions.” And they weren’t particularly personal or intrusive. But she said, “I actually think that I want to talk to Frank first and make sure it’s okay that I talk to you.” I said, “Absolutely—you have to be completely comfortable in this.”

So we went away for a little while and she got back to me and she said, “I’m going to email introduce you to a bunch of people.” And so she introduced me to five people, including Frank (again). And then Frank emailed me right after and said, “Great, let’s talk this morning at 10.” It was 9:40—I was in my pyjamas, just sent my kids off to school. So I essentially had to make my pitch to him without any notice, which was probably for the best, actually. I just pitched what I wanted to do and he said, “Okay, you should come over and we should talk.” So it was really Shauna Levy, who was president of the Design Exchange at the time, who was my gatekeeper.

The only other person that I cold emailed was Bernadette Moira, who was the editor in chief of Fashion magazine at the time. And I just emailed her and I knew that she was one of Frank’s friends so I felt comfortable doing that. She got back to me the next day and said, “Sure, c’mon in” and she allowed me to interview her and she brought out the magazine’s archives and we looked at them together. She was great! She was definitely not The Devil Wears Prada kind of editor—she was really, really helpful. It really got rolling, and once it got rolling it kept moving.

When I was reading about MᐧAᐧC’s early years, I couldn’t believe that Frank Toskan’s brother-in-law (Victor Casale) was studying chemistry at U of T at the time, and that’s how they managed to start physically making their cosmetics.

It’s very much a story of just the right people at the right time and the right place; I keep simplifying it to that. But Frank never really thought about “creating cosmetics” because he was just a creative person. And when he wanted to start playing with things, you know, Vic Casale just happened to be there because he had been dating Frank’s sister for such a long time. So that relationship really worked. I met Victor Casale a couple of times. He was (and still is) the chief chemist at Cover FX Cosmetics, so he invited me up to their head office. He said, “I want you to come here and see this because what it looks like here in the Cover FX office is essentially what I’ve done at every office and factory facility that I’ve ever had since the first one with MᐧAᐧC.” So when I described the MᐧAᐧC factory in the book, it was really me describing what he showed me. He said, “we had a table that looked like this, and instead of this at the time we had this because this didn’t exist yet, and the walls were always this colour and the shelves always looked like this, etc.” So it was really cool to go behind the scenes there and see that.

While I was reading, especially in the beginning, I kept waiting for the overall flaw of MᐧAᐧC. They were so good to their employees, they had complete transparency about their products. And I was thinking, “Are there any flaws to this company?”

I’m sure there were. Nobody’s perfect. But that’s not what people remember, that’s not what people take away from it. Because I think they knew that even if that were the case, what they were doing was extraordinary and different. And they were so excited to be a part of it. People didn’t tell me any of those stories, not really. But surely they did [have flaws]. When I talked to John Demsey, who is the Executive Group President of all of the Estée Lauder companies globally, and explained my argument, he said, “that’s interesting. You know you could have written a very different book.” And I don’t know what that meant. But if he was implying that it could have been a type of gossip-mongering, well that’s not what I’m interested in, as a scholar; I’m looking to explain, not just to describe or be scandalous. Leave that for others.

In a recent interview with the University of Toronto, you say that you generally find the commodification of social issues objectionable and that your previous research on cause marketing has shown you that such campaigns are often disingenuous. Has researching MᐧAᐧC shifted your perspective?

Mostly I find cause marketing objectionable in almost every instance that I come across because it’s always about making money, and it’s usually just so contrived and obvious. And what was so interesting to me about this story [about MᐧAᐧC] was that it was so organic. You could never say, “Here’s a model of cause-marketing or corporate philanthropy that we can study and learn from and replicate in other companies.” But MᐧAᐧC is the exception. I find the exception here to be so interesting. Generally, I don’t know if it is even possible to have real social change through capitalism. I think there are differences that can be made, there are things that can be made better. I think companies truly believe that there are things they can improve on, but the system is made up of exploitation, so it’s not truly possible. I’m interested in the exceptions. That’s why I found the [recent] Gillette ad quite interesting—because it was different, but also because it was potentially quite damaging. Those are the interesting things when the campaign doesn’t serve the obvious purpose—it looks like it’s counterintuitive or counterproductive.

I have some ideas about other types of marketing enterprises that have sprung up in a more organic way that I’m thinking through…It’s out of the left-field so I won’t talk about it, but I was thinking through how this example of an online community and a type of corporate philanthropy and retail and sponsorship and advertising has come together and still seems so pure. And I just don’t know if that’s true or even possible. I have to think through this example.

And consumers are so onto it now, right? You know in the earlier days—and you can go back as far as the 90s with breast care philanthropy and red ribbons and stuff like that—people really didn’t know what else to do. They thought that putting $5 in a box and wearing a red ribbon actually helped somebody, or contributed to research to figure out how to get rid of AIDS. But I think consumers now are pretty much onto it. Everybody has a cause marketing campaign, everybody has some kind of philanthropy that’s just part and parcel, it doesn’t really stand out. There has to be the next iteration.

You talk a bit about Product (RED) in your introduction and how that campaign has drawn a lot of criticism since it began in 2006. For instance, many accused the campaign of distancing consumers from the material reality of AIDs in Africa. Do you find that AIDS awareness has declined over recent years?

Totally! So Product (Red) was absolutely shameless. Its business model was: “We are totally a capitalist project, we are a marketing initiative. We are not hiding the fact that we are going to sell you cool stuff and some of that money—maybe a little, maybe a lot—is going to go directly to the Global Fund.” And because they used celebrity and flashiness and spectacle, it got a lot of attention in the early years.

But it’s not top of mind anymore, and some of the things I have heard have indicated that it might actually be possible to eliminate AIDS in the next couple of decades. Now we have people who live with HIV for years and years and years, and it’s managed as a chronic condition. It will get there one day. It’s just that the meanings around AIDS have changed, you know? It’s now treated more like the medical condition that it actually is. That’s not to say that there’s no stigma around it—there’s still tons of stigma around it—but it’s not so shocking because it’s not like it appeared out of nowhere as it did in the 80s. It was very much tied to the state of gay rights and gay activism at the time and now that situation is very different as well.

Do you think the VIVA Glam campaign was truly one of a kind? Have you come across any other brands—contemporary or otherwise—with that level of transparency?

There really aren’t any [contemporary examples]. VIVA Glam is totally unique and probably would never be envisioned in the same way again. A lot of people told me that; they said that companies would never do that anymore. The relationship MᐧAᐧC has with all of its department store partners would never go for that, at this time. And they have to evolve with the times. They have changed their slogan from “all ages, all races, all sexes” to “all genders,” which is a good move. And I think they’re rethinking some of the initiatives that they do. I read something very recently from Nancy Mahon, who is the executive director of the MᐧAᐧC AIDS Fund; they are rethinking how they talk about AIDS now—and they have to because the meanings have changed. But they still fully intend that VIVA Glam remains a fundraising project with a 100% [sales donation] model.

Apart from aligning with social causes, MᐧAᐧC has debuted so many themed collections featuring iconic pop culture personas and images: Barbie (2007), Hello Kitty (2008), Wonder Woman (2011), Betty & Veronica (2013), The Simpsons (2014), and several Disney characters. What do you make of the intersection of MᐧAᐧC, a historically alternative and rebellious brand, with these incredibly mainstream icons?

Yeah, it’s a really interesting thing to think about! So back in the day, in the early 80s/early 90s, MᐧAᐧC would release two collections a year. I used to have a MᐧAᐧC girl that I would go to at The Bay at Yonge & Bloor—her name was Tracy—and I would definitely go in and see her when the collections came out. I would still shop a little in between, but that was it. And I would buy pretty much everything—I didn’t have a lot of money then, but I would buy all the things. So this move to have new collections come out [so frequently] must be exhausting. Phillip Ing, who was the director of all the Fashion Cares shows and who was very much involved in coming up with these new concepts, has stepped away from MᐧAᐧC now. But I think it must be exhausting to keep tapping into popular culture and finding the “new.” Because fashion is always about what’s new and telling people what they like, and telling people what’s hot. And so I guess I would question whether MᐧAᐧC really has an identity as an “alternative” brand [anymore]. I don’t know if that’s true—some of these smaller make-up artists lines like Morphe offer a similar aesthetic [to MᐧAᐧC] at about a third of the price. I think it’s hard to really consider MᐧAᐧC alternative now. It is the #1 prestige brand globally, so there’s no way it can be a subculture anymore.

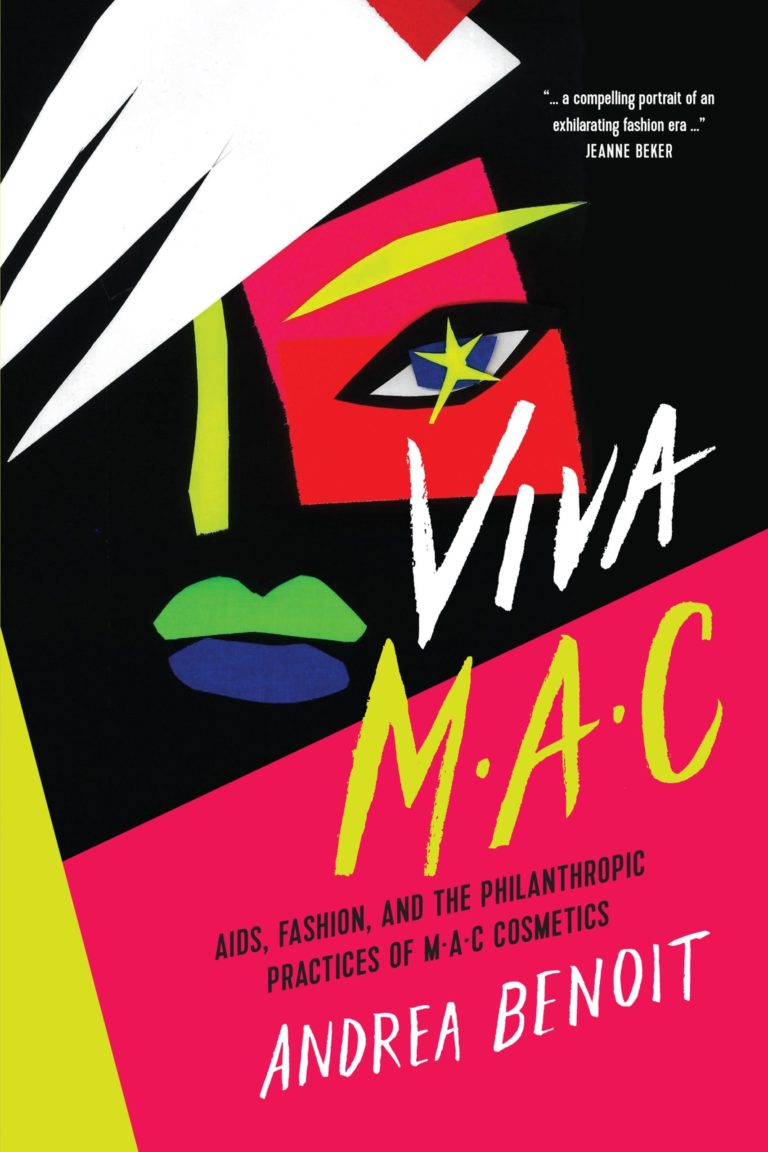

I love the cover illustration for VIVA MᐧAᐧC; did you always envision that Donald Robertson (an artist who contributed to MᐧAᐧC in its early years) would create the art for it? How did you go about finding him?

I just reached out to Donald—to his agent or his gallery, I can’t remember. I said, “I want to talk to him, can you tell me how I can find him?” And it was just the easiest thing: I emailed him, and he got back to me right away and said, “Sure, happy to talk, my assistant will set it up.” So we had our interview. And when it came time to do a [book] cover, I said, “Listen, it makes total sense, it would be the best thing ever, it would be so amazing, if you could do this.” And he was like, “Yeah, sure, no problem.” I gave him the spec, and he knew exactly what I was after. He does a lot of collages now, but he did a lot of collage in the 80s—Frank had some of it still, that he showed me. So Donald sent me a [photo of his work] and said, “If you like it, then I’ll send it to you.” And I said, “Well, I insist on paying you for your art.” And he said, “No, don’t worry about it”. So I never did pay him, and he never did ask for it.

A couple of weeks later, the original art showed up on a piece of Bristol board folded in half. It’s construction paper and painters’ tape and that’s about it actually! So we framed it and it’s in my living room. And the art directors at the University of Toronto Press chose to manipulate it a little with the title, etc. They took the chin and wrapped it around and picked up on the green to make the spine. But it’s basically the same. I was so proud of it and so thrilled with it, it’s just so…unusual.

That’s exciting! Especially as you talk a bit in your book about how Frank Toskan was initially resistant to having any kind of face associated with MᐧAᐧC. But then they brought in RuPaul for the VIVA Glam lipstick advertisement, which is such an iconic poster.

At the time—and in my book I probably understated it—it was just so shocking and so risqué. We live in a very different world today—in the mid-90s, this poster terrified people. The one anecdote that I just find the best was from Valerie MacKenzie—she was the marketing person who would take all these phone calls and customer complaints and liaise with the public in various ways. So one day somebody called and said, “I want to talk to the owner.” And she said, “Well, the owner’s not here, how can I help you?” And so the person said they were really outraged at the [VIVA Glam] ad and yada yada yada. As she had done many times, Valerie explained what the point of it was, and that it was a fundraising product, and that the ad was designed to draw attention to it. But the customer still wanted to speak to the owner. Frank’s sister had come in, so Valerie passed the phone over to her, but the customer still wasn’t satisfied! And Frank just happened to come in during all of this. So she handed the phone over to Frank, and he listened very carefully and very quietly, and then he said, “Well then you can just fuck off and buy another brand.” And he meant it! [laughs].

That was the attitude they all took, with the department stores, with management: “If you don’t like it, you can fuck off, because we don’t need you.” And as it turned out, the department stores really needed MᐧAᐧC. But I think that’s an attitude that they truly believed: “We are going to do what we’re going to do, and if you don’t like it…we don’t care.”

What inspired you to dedicate your book “to the underdogs”?

So that came out of when Frank was telling me that MᐧAᐧC made it a mission, in their early days, to hire creative people, in whatever capacity—whether they were artists or painters—and to let them create and be themselves. But he recognized that those people have always traditionally been on the margins, and definitely in the 80s, gay kids and gay young people (we wouldn’t have called them LGBTQ+ people yet) struggled to find a place. So he welcomed all of the variations of people who were out there and who believed in what he believed in. And he called those people—who didn’t fit in and might not get opportunities in mainstream employment—the “underdogs.” And I felt like they were representative of all of the people who were ostracized, who were rejected, who died alone—all of the people who didn’t fit in and were made to feel like it was their fault. I just wanted to honour that. Because while this is a story about a corporation doing a good thing, a lot of people suffered so much in the 80s. And I read all these stories; they are all in the archives, these memorials, these horrible stories of (mostly) young men, who were rejected by their families, when their families found out that they were close to death or HIV positive, people whose new families were their friends, people who lost their jobs because nobody wanted to be around them because they thought that being in the same room would make them ill, people who had nowhere to go because they lost their apartments because they had no job, people who were taken care of by their friends around the clock because there was nowhere else to do it. These were terrible stories, and I felt like collectively all of those folks were the underdogs. And I want people to know that. Because what the commodification of something like this [AIDS] does is it removes that history and replaces it with consumerism and pseudo-feel-good moments, and that’s…wrong. And it’s important to not forget that history.

Andrea Benoit is currently the academic review officer at the University of Toronto in the Faculty of Arts and Science. She is also an adjunct professor of Media Studies at Western University.