Review of Fuse

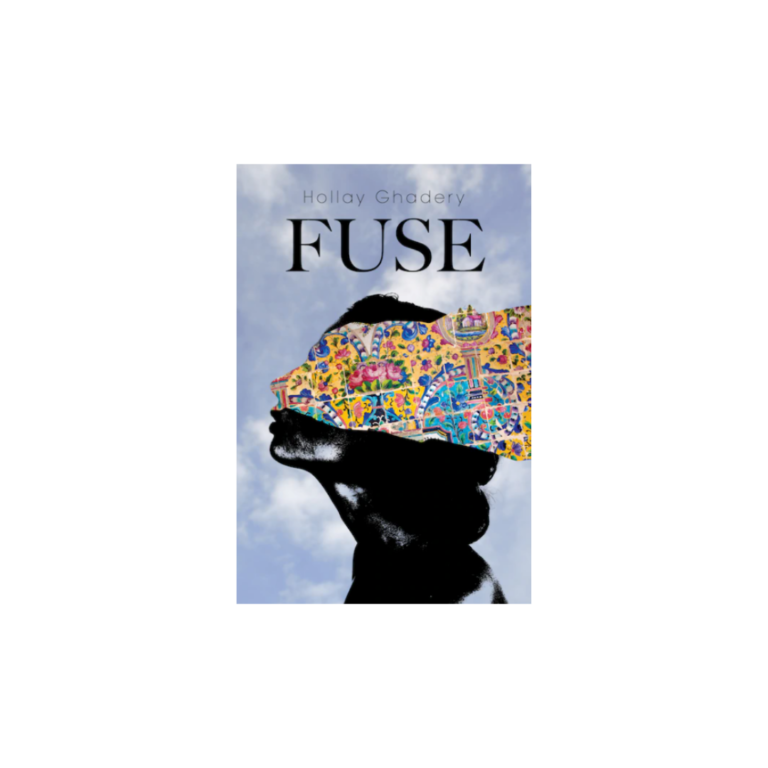

Guernica Editions. 2021. 170 pages.

For many of us who grew up in multicultural homes, identity is a complex, shifting experience. We often come to understand ourselves as patchworks: a little of this, a little of that, a whole lot of things we wish we knew more about. Our identity is thus an intersectional labyrinth of class, gender, race, and culture where we are everything and nothing at the same time. For Hollay Ghadery, this sense of multiplicity can be exhausting: “It didn’t occur to me then that it was alright to live in the space between states that are precisely defined. I felt trapped by the uncertainty, which I’d grown up thinking was synonymous with weakness. You were one thing or the other. There was no grey area.”

In her debut memoir Fuse, Ghadery explores her identity as a half Iranian, half white (British Isles) woman through several defining moments over the course of her life. Like the duality of being biracial and bicultural, this book is written in non-linear vignettes that jump back and forth between present day Hollay—who lives with her husband Matthew and their four children in Oakwood, Ontario—and the Hollays of the past: as a child desperate to learn Farsi (the native tongue of her father) much to the discomfort of her English-speaking mother; as a young woman leaving home for the first time and falling into toxic relationships (both with self and with other) that soon beget substance abuse and eating disorders; and as a newlywed navigating the strain of familial, parental, and cultural spaces. The memoir narrativizes Ghadery’s life with exceptional honesty and exacting detail, meditating not only on identity, but also on the female biracial body and mental health.

In the first chapter “Waiting for Wonder Woman,” Ghadery chronicles a movie date with her five-year-old daughter Nuala, whom she takes to see Gal Gadot in DC’s Wonder Woman. The movie, which was released in 2017, has been hailed as an important step for women, paving the way for more female hero leads; but as Ghadery realizes, this is only one side of it. “Because it’s always the same kind of woman; the same kind of body….[and] part of me didn’t know why I was surprised by this anymore: the narrow idealization of female beauty, and my furious, impotent response to it.” This observation quickly incites a childhood flashback: “Me at twelve: Pacing the family room and sobbing because I’m so fat…I was crying because I’d just read another Seventeen magazine. It had praised the same long, lithe girls who looked nothing like me.” Ghadery digs into her relationship with her body—even unpacking her own fatphobia in a later meditation called “Vanity Muscle”—and spends much of the book exploring the nature of feminine sexuality and the ruthless sentencings of women deemed too slutty or too prudish both in Canadian and Persian cultures.

At the root of this memoir lies a consideration of multiplicity, what Ghadery links to “biracial identity disorder,” or the experience of a non-fixed identity that is often prevalent in biracial women. A through line, BID grounds Ghadery’s questioning of her self-image, which she sees as fragmented and in need of perfection, and her familial dynamic, which is complicated by her father’s traditional values and her mother’s dismissive attitude. Ghadery calls herself “someone practiced in the art of self-deception,” but each of her anecdotes express humility, resilience, and an utter willingness to confront herself. Even when Ghadery explains how her OCD has propelled a lifelong fixation on cleanliness, or how she would silence her insecurities with the refrain “drink til you’re hot,” or how cutting herself in the midst of a lover’s spat led to her first therapy session, she never loses the sincere, vulnerable account of who she is. As Ghadery finds, having no-fixed identity forces us to choose who we are almost every day. “And no matter how much I think I know exactly who I am, the world will continue to break me down, and force me to choose again.” But choice, Fuse suggests, is exactly what empowers us. The silver-lining of multiplicity is that we do not need to be confined or restrained by our identities. Instead, we can begin to live outside the strict categories and labels that we are often boxed into.

This short, evocative memoir offers biracial and bicultural women everywhere the chance to feel represented and heard. Ghadery gives us her entire heart in this book—beating, bloody, and full of bravery. Her self-editing tone and non-linear narration create a ripe playground for pop-references, dark wit, and tired confessions of a rockstar mother. Ultimately, Fuse reminds us that despite the many challenges of existing in multiple identities, we are still whole, undivided people. We cannot be shattered.

[TW for self-harm, suicide, eating disorders, substance abuse, mental illness.]