My father walked me to school on my first day of kindergarten, and in his limited English, introduced me to my teacher, Mrs. Smertes, a gray-haired, severe looking woman with enormous glasses. In Italian, the only language I knew, he assured me I would be fine, reminded me to listen to the teacher and promised he would be back to pick me up at lunch-time. In the late 1950s, there were many Italian immigrants in our small Northern Ontario town, but it was my bad luck that none of them were in my class.

The classroom was long and narrow with a door on either end. Most of the other children didn’t look or sound like me. My mother spent what felt like hours combing each section of my dark locks with a tail comb dipped in a glass of water, curling my dark hair around her fingers into long ringlets. These children had lighter and straighter hair. I couldn’t understand what they were saying and had difficulty pronouncing their names, most of which had no vowel at the end. Even their laughter sounded like it was in a different language. I was sure that much of it was directed at me.

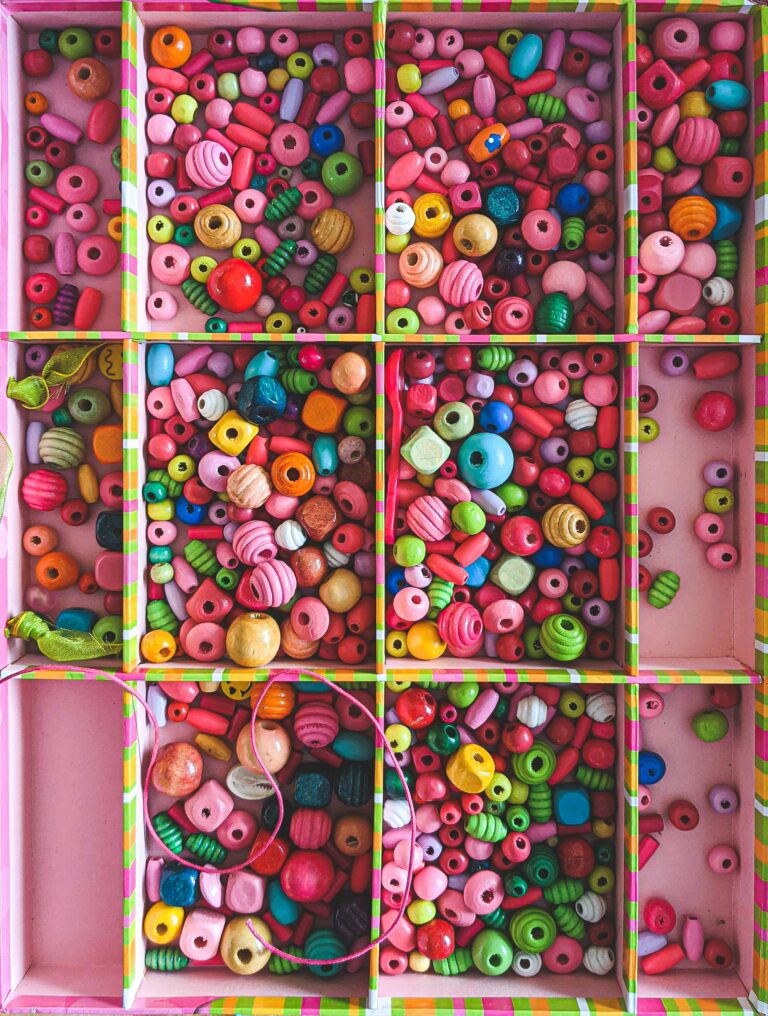

The long tables in the middle of the room were adorned with string and jars of pretty coloured wooden beads, and I wondered if I might be able to touch them, but didn’t know how to ask. As Mrs. Smertes started the class, I watched with envy as the other children listened. I wished I could borrow some of their comprehension. She was directing us to do something, but I had no idea what it was. This feeling of isolation was as foreign to me as were the words, which were short and harsh and when strung together, with no lyrical timbre. As I remained rooted to my spot while my classmates got up to obey instructions, the children stared, giggled and pointed in my direction. Mrs. Smertes glared at me, her bushy eyebrows scrunched down below the rim of her scary glasses, and raised her voice. An increase in volume didn’t make the words more understandable. She grabbed my arm, and I started wriggling, whining and wailing, none of which, it seemed, were acceptable responses, and she pushed me into a chair in a corner, with my back facing the room. I had had enough. I ran to the door closest to me, convinced that I could escape and find my way home. She was too quick for me and locked that door as I bolted toward door number two. She was pretty fast for an old lady and managed to wedge herself between me and the door, locking that one too and dashing my final hope of getting back to my father.

By the time the class ended (I was thankful it was only a half-day), Mrs. Smertes and I had come to an unspoken agreement. I would stop trying to escape and she would stop punishing me for my lack of English comprehension. This was a relief because words were what had gotten us into trouble in the first place. Once the other children left, I made my way over to the beading table after stealing a glance at my teacher to make sure her eyebrows were straight again. While I waited for my father I threaded in silence, savoring the feel of the beads, exercising the right to choose any colour I pleased, in whatever order I wanted. When he arrived, I didn’t want to leave. I wanted to prolong this moment during which the smooth beads were a perfect fit for my hands, the colours were playful and inviting, and I no longer felt different from the other children. The beads allowed me to make choices without judgement. I could play in my new surroundings without feeling the need to conform to a standard set by strangers.

The beads didn’t care what language I spoke.