Review of Are You Willing to Die for the Cause?

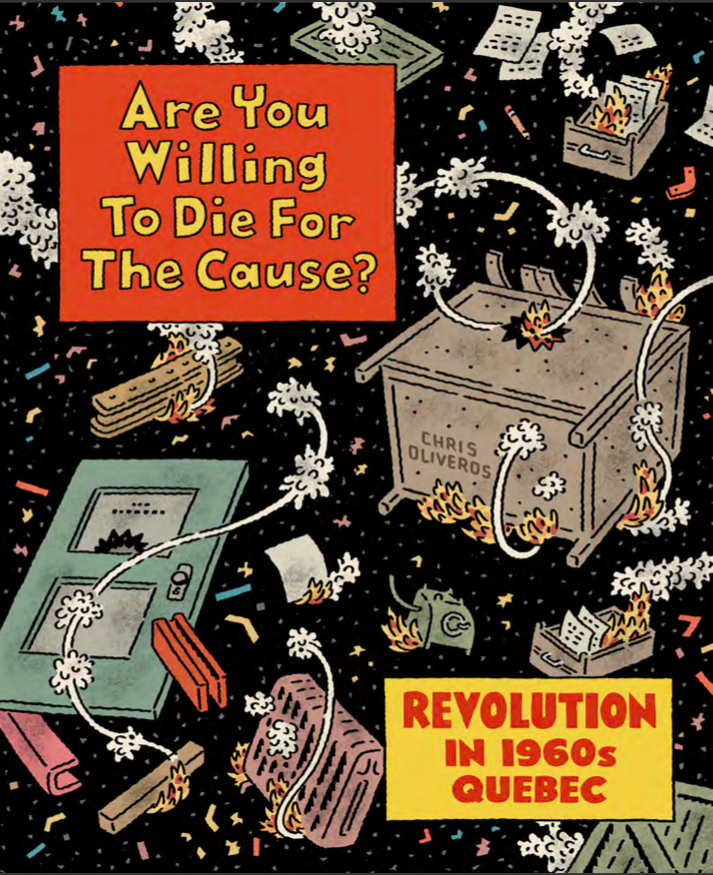

Drawn & Quarterly. 2023. 176 pages.

Murder, bombings and political kidnappings in the name of justice for all. Will violence ever give us the peace we need? Québec-born author and cartoonist Chris Oliveros founded Drawn & Quarterly, dedicated to publishing cartoonist’s work. Held in high regard for its dedication to allowing artistic autonomy to flourish, it has been nominated for several awards, including the Man Booker Prize. Oliveros’ own graphic novel, Are you Willing to Die for the Cause?, gives a brief history of the formation of Le Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ), a political protest group, and its infancy. It highlights the key players like mayor Jean Drapeau and original FLQ founder George Schoeters, through a series of documentary-like interviews to explain what started out as the “October Incident” and eventually became the FLQ. This historical memoir paints the backdrop of Québec in the 1970s as being hostile to the French-Canadians living there under English colonialism. The sparks of rebellion started with the French-speaking citizens being denied employment, suitable housing and the same level of legal recognition as their English-speaking counterparts. As tension grew, the group’s goal became more ambitious to make Québec independent and socialist. To ensure negotiating power against the ruling government, these French-Canadians orchestrated political kidnappings, demonstrating the gravity of the situation.

Oliveros starts his graphic novel with interviews between the mayor, Jean Drapeau, editor-in-chief of the Le Devoir newspaper, Claude Ryan, and main leader of the FLQ, George Schoeters. It becomes immediately clear how skewed the group’s actions are. Following our biased narrators on either side of the rebellion, the self-serving nature of each group looks to paint themselves in a better light while dealing with the “terrorists” of the opposing faction. Both Claude and Jean remember the FLQ members as failed terrorists and exaggerate the first attempted bombing attack. Then we have George, interviewed from exile, explaining their plans and how they failed spectacularly, causing little to no damage except litter to be cleared.

Through different perspectives, we witness the development of the FLQ. George Schoeters shares his ideas with fellow French men about the injustices they suffer because of their mother tongue and heritage. Having secret meetings in his family apartment, they discuss how they can force a change in the government to better their lives. As members find hope in their ideals, the plans for attack come to life. And yet, because of their failed bomb attacks on different armories around Québec City and an accidental murder, George Schoeters is imprisoned and usurped from his position as leader. His original ideals of scaring the government into change are mutated and now take a life of their own, with the members becoming bolder and their demands getting louder. With François Schirm taking over as the new commander of the movement, he radicalizes the group; believing that his dreams are to be achieved through more reckless and morally gray methods. He recruits amateur fighters and teenagers to join their guerilla training camp outside the city limits. Here, with limited food rations, members, and ammunition, they were encouraged to hold out for resources from their hidden sponsor, Fidel Castro. From this point forward, the group stages a series of robberies, mailbox bombings, and earns itself a reputation for being impulsive murderers as tensions continue to rise throughout the city. Following the climax of innocent people being killed by their bombs, the FLQ members are being hunted down. Oliveros ends his graphic novel with a cliffhanger, leaving us to wonder what will ultimately become of the group’s agenda.

I found Are You Willing to Die for the Cause? an interesting introduction to the history of the FLQ and Québec for a novice. I find North American history to be more dull than most, but this was a surprisingly easy read. Oliveros gave enough background information to give the reader a soft launch of the rebellion without drowning us in the nitty-gritty details. The ruling government typically paints the resistance as dangerous and erratic as a reaction to save face or undermine the cause. The ongoing wars and mounting tension of today’s global politics show how little we learn from our history. Violence seems to be the “most reliable” means of forcing oppressive agendas forward and anyone challenging this becomes a problem that needs to be suppressed. How dare the less fortunate demand to be treated as equals, let alone human beings? This steadfast determination to vilify them rather than see them as a response to injustice gives the FLQ more of a foothold. The rebels became more relatable. I was more sympathetic to the cause. While the idea of bombings and robbing armories leaves much to be desired, this gives context to the level of desperation the group felt. By any means necessary, they were going to improve their lives. Humanity’s masked darkness relishes in embracing violence regardless of the issue or century. Humans pride themselves on being the “smartest” of Earth’s living creatures, yet our love for violence directly opposes this. Of all the species on the planet, we are the ones that actively attempt to develop specialized weapons and tactics for wiping our kind out. So much so that it is one of the few things we have mastered.

We empathize easier when we can recognize them as one of our own. A sense of familiarity in mannerisms, language and features can subconsciously make us more accepting of people. Likewise, the more different they are, the more hostile we become as part of our innate desire to keep ourselves safe. Countering this by using a muted color palette, the scenes and characters could be from almost anywhere in the world. The characters are cartoony enough to make graphic scenes less traumatizing and allow the reader to fill in the blanks. Oliveros cleverly leaves enough ambiguity that you can impose yourself on the characters and feel more or less connected to the problems they face. This space for the possibility of intimacy is a mirror to the truth of how willingly we discredit information that causes us discomfort. Rebellions and wars are guaranteed to show the worst in us and polarize communities completely. Its blunt force attack to rearrange fine china. The choice to frame the politicians at eye level, in their orderly offices, highlights how far removed they are from reality and gives them a sense of authority. Given today’s global climate, I see how our unwillingness to admit to injustices we passively take part in parallels here. When the mailbox bombings go off, the crowds of onlookers continue to blame the rebels without a single thought of their contribution to their suffering. Drawing the rebels from a higher perspective all clumped together gives the illusion that they are a brainless mass. It highlights how we instinctively think of anyone that disrupts daily life, regardless of how corrupted it is, as the source of evil. Being passive supports those intent on killing the suppressed and we like to enjoy the first-world privileges of deniability. We get to pretend we are still good people, that there is really nothing we can do to sway the governments that we put in charge. Even when we are actively involved, we often comment more on the actions of the repressed rather than the roots of the problem.

Despite Oliveros’ focus on the themes of revolution, the characters remain two-dimensional as they carry out the retelling of events and are sentenced to their fates of prison or suicide missions. There is little insight into the character’s personal headspace, why their motives change or escalate outside of the fight for the cause. There was not enough of the human psyche on display for me, which I think could have helped with sympathizing with the FLQ as they got more desperate towards the end of the novel. The emotional weight of imagining what would have caused ordinary people to plant bombs is left up to our ability to empathize. As a commentary on the history of Le Front de Libération du Québec, it gives a wider overview of the whole situation, prompting deeper discovery to curious readers. Are you Willing to Die for the Cause? offers a snapshot of the leaders, the government’s view and other instances of humanity in these situations. While it reads as a documentary of the events, there are glimpses into the personal life of some characters that humanize the cause. Seeing the damage it caused to George Schoeters’ family, we remember that these were ordinary people trying to better their situations. We see his wife trying to maintain a distance between the secret meetings and their children. The explosive devices being stored in the pantry next to the baby food highlight how determined Schoeters was to change his situation. These rebellions are never formed in a vacuum and people involved have a normal life like you and I do. This is scary to think that one day the thing that tips the balance can make you less human and simply a part of the problem.

A steady and trying chain of events explaining the beginnings of the fight for equality continues to echo through history, even today. The basic human need to integrate into society and make a life worth living continues to be the driving force behind revolutions, wars, and reconciliation for peace. While each side of the coin can claim a land as home, the true conflict is how it can be shared equally. Given the flawed temperament of human nature, this is likely to be a continuous hallmark of our shared history. Humanity has proven repeatedly how incredible our feats of intelligence are at making the impossible an everyday reality. We have been to the moon, cured diseases that killed millions and yet we resort to the intelligence of stones when it comes time to dealing with our fellow humans as equals. We believe we are always in the right because our story is more personal than our neighbors. We lack trust and insist on keeping our feet on each other’s necks, just in case. Stories like Chris Oliveros’ Are You Willing to Die For the Cause? help map the continuous reshaping of cultural climates and societal norms as history predicts the future. Will we ever give emotion and intellect the same power to promote change as we do our guns and violence?