Review of Scenes from the Underground

Anansi Press. 2022. 153 pages.

Author Gabriel Cholette disappeared into the queer club scene of the pre-pandemic era. Overcome by youthful optimism, he ran to metropolitan paradises like Berlin, Montréal and New York with only one goal in mind – for discovery. Chasing needlessly after fading faces, wandering around the Berghain or Glitterbomb, in any attempt to “habituate [his] eyes to the darkness.” We are often driven by curiosity, and for Cholette it was no different. In a setting that feels euphoric, disorientating and ever-lasting, he weaves aimlessly through the dark rooms and bathroom stalls, caught in “a strange place between desire and reality.”

In Scenes from the Underground, we are immersed in a vibrant atmosphere where we are obliged to find meaning under the blaring dubstep music that drowns out our anxieties and existential dread of the outside world. His poetic articulation consummates a transcendent experience where the party drags on into the early hours of the morning. Time feels practically infinite. Through serotonin highs and hangxiety lows, he graciously brings us along for the journey, sharing even the most intimate details of his encounters

Cholette’s debut memoir is a collection of brief, evocative descriptions that transport the reader into scenes that may seem unconventional, but are undoubtedly intriguing. While navigating each city’s dynamic nightlife, Cholette explores themes of sexual identity, rejection, drug use, and anonymous sex from a queer and introspective lens. As he jumps from one place to another, a globalized club culture permeates every scene. You’re dancing, sweaty, and grinning like a fool along to that same damn techno beat. With each tantalizing story, the title encapsulates the moment perfectly, entrancing the audience. Examples like “Goblins,” (which he affectionately refers to the people around him as, including himself) or “Gay Falls,” (aka Chute Sainte-Marguerite, where much publicized nudist raids took place), reel us in and entice us.

In a theatre criticism examining aspects of queer nightlife, Kemi Adeyemi, Kareem Khubchandani, Ramon H. Rivera-Servera explain that there is “a sensual and social bliss offered by queer leisure after dark.” When entering designated queer spaces, there is a freedom – a weight lifted off our shoulders. There is no fear of judgement or the possibility of being harassed, because there is an assumption that everyone entering those spaces respects queer people. And so, we feel comfortable expressing our authentic selves. That self-discovery is the most valuable thing to hold on to. These spaces allow Cholette to explore his sexual identity and connect with other queer people all over the world, allowing him to feel liberated. At the same time, this addresses a need for more queer spaces that create this kind of inclusive environment that embraces unadulterated sexual exploration.

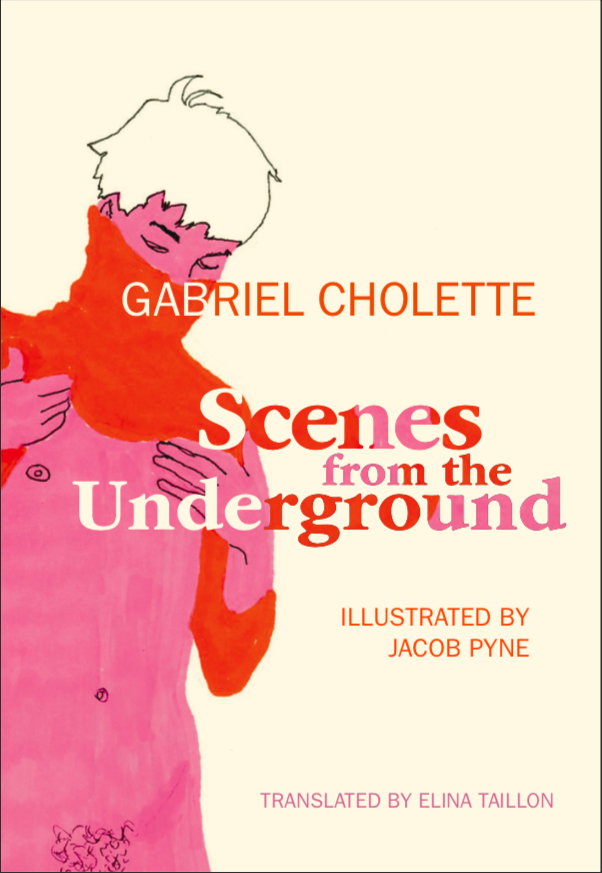

As his work covers experiences from within the gay community, the creative team is made up of a queer trifecta, including Jacob Pyne and Elina Tallion. There is a sense of relatability and understanding as each artist brings their own individual experiences that come together in a beautiful manner. It is well-thought out and cohesive. Since they decide how the narrative will be told and how it will be presented to an audience, it is important that they represent the needs of the community.

Scenes from the Underground is depicted not only from a queer perspective, but from an Instagram generation. Instagram offers a limited and curated glimpse into the lives of strangers. This is how Cholette began his memoir, starting with Instagram-style vignettes on an anonymous account for his friends (@carnetunderground). This is where he would share little intimate details of his life, accompanied by Pyne’s drawings, and snippets of his observational writings. As the book took form, he began to reveal himself more candidly, taking ownership of his zesty prose and refraining from hiding behind himself.

Pyne’s erotic illustrations, depicting unabashed nudity, add to the book’s appeal and help center us further into the narrative that Cholette is telling. They not only reveal elements of the queer experience, exploring nightlife and his interactions with others, but they also evoke a sacred intimacy. His art allows us to feel closer to our own bodies and the desire which we are eager to share with others. His use of touch creates this illusion of two bodies intertwined, underlining this deep need for intimacy that Cholette so desperately craves. That we all, on some level, hope for.

Physical touch, though not always sexual in nature, plays a critical role in most relationships. It’s a love language that has a person acknowledge their partner(s)’ presence as something welcomed. The kind that may satisfy sensual needs or offer safety to a partner. Under flashing lights, touch grounds Cholette further in these club spaces, but it is also something that he can’t quite grab a hold of, slipping through his fingers all too easily. There is a harsh paradox of craving that intimacy, but receiving it in only small doses. Pyne’s drawing for “Queen of the Toilets” alludes to Cholette’s desire for human connection. The two bodies in the original image, one dark pink and the other a much lighter hue (supposedly illuminated by the club’s fluorescent lights), mimic but only one figure casting a shadow of themselves. This could be perceived as vice versa, depending on how you look at it, but the intention is similar, demanding the need for another to be close. It personifies that feeling of loneliness while standing right next to someone else. With touch and simultaneously, without.

Queer artist, Richard Dodwell, says, “loneliness – like all grief – is a queer experience.” We can see this clearly articulated here. Cholette instills a chilling and dissociative solitude in his words, alluding to a distinctive feeling of isolation. It is the kind of numbness that is experienced in the centre of a chaotic dance floor as soon as reality sets in – a sense of unavoidable and ever-looming dread. This concept of rejection is recurring. The stories in Scenes from the Underground give off a sense of endless exploration, as the majority of them take place, primarily describing his nights out in the back rooms of clubs and raves. He comes to terms with “meeting people left and right…[with]…the risk of it stopping there,” accepting an inevitable end. Characters like Edu, Bert, Florian and Ben that he mentions all fit into a fantasy, but they seem to evaporate as soon as the party ends or as the drugs lose their effect. These blissful moments morph into faceless blurs and snippets of recollection. Affection is so fleeting, and Cholette finds this out the hard way. There is a looming quietness in the juxtaposition to all the chaos. We are all just dancing alone, absent-mindedly, waiting to be seen, felt, or understood in some kind and soft way.