Review of At Night All Blood is Black

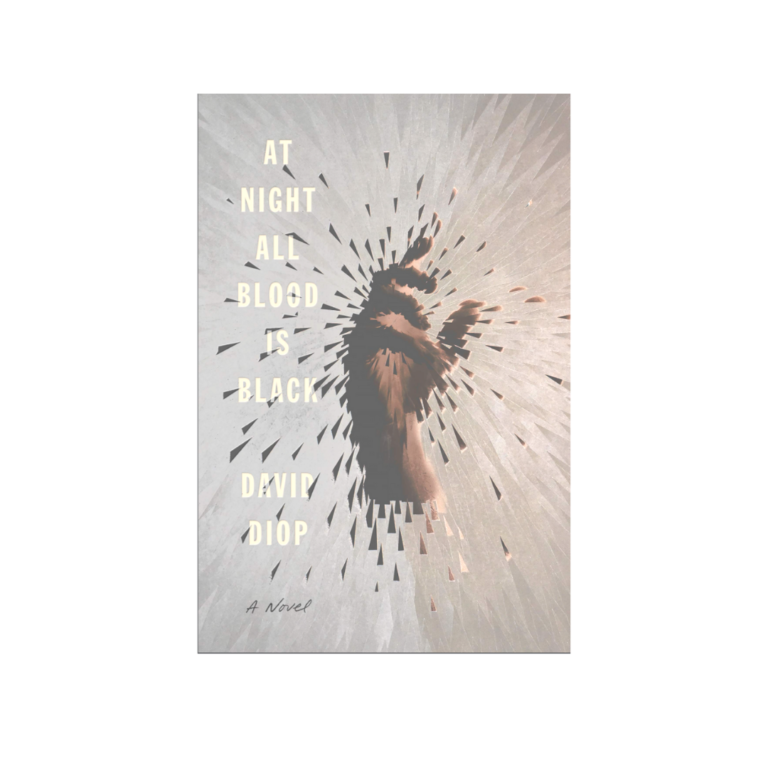

Farrar, Straus And Giroux (FSG). 2020. 160 pages.

Revising history is seldom a simple feat. One has to consider what has been told, how it has been presented and, most importantly, who has been controlling the narrative. David Diop attempts to wrestle this alteration of history in his novel, At Night All Blood is Black, by creating a dark fictional account of the French army during the First World War. Diop’s account is so detailed that I could imagine myself reading it as a historical first-person account.

Diop’s novel centers around a facet of French history that has been typically overlooked by history books: the life of African troops who fought for France in the trenches, during the First World War. These soldiers were recruited from all over West Africa, but their perspectives are pointedly missing among letters and accounts from French soldiers. Diop creates a narrative for this missing piece through the protagonist Alfa Ndiaye, who has been sent to war with his best friend Mademba. After witnessing Mademba’s death, Alfa takes revenge by killing opponent German soldiers, cutting off their hands, and keeping them as trophies. The novel follows Alfa during his time in the trenches through to his struggle to unravel the person the war transformed him into.

Throughout the novel Diop demonstrates the theme of rivalry, both between the French army and their opponents at war, as well as between Alfa and the non-African soldiers. There is a constant argument against reverting the war to a “good versus evil” debate. However, Diop ensures that the narrative isn’t encompassed by trivial rivalry. Through Alfa’s mental deterioration as the narrative progresses, Diop argues that everyone loses in war.

The novel begins in the middle of a battle, and the reader is automatically thrown into the trenches. We see the tragedy of witnessing a death for, what it seems like to Alfa, no reason at all. The search for someone to blame is embedded into Alfa’s story. Diop writes: “they want someone to blame, they’d rather think that the enemy bullet that hits them was directed, guided by someone cruel, malevolent, with evil intent.” Diop enhances the theme through Alfa’s grotesque removal of fellow soldiers’ hands, a symbol of his search for blame in the endless mass of identical soldiers. The war has infected him, and he has departed from who he was before.

The theme of revenge allows Diop to display war as a disease, something that infects individuals, and transforms them into an unrecognizable creature. Through gruesome scenes of Alfa acquiring dead soldier’s hands, Diop’s (and well translated by Moschovakis) hypnotic prose enhances how poisonous and all-encapsulating war is for these soldiers.

However, there were points where the graphic prose pulled me out of the narrative. This was particularly in scenes where Diop would use repellent imagery regarding women, seldom when an actual woman was present. The most obvious offender was when a trench is described as the “slightly parted lips of an immense woman’s sex,” which was more difficult for me to stomach than the slow, bloody deaths of soldiers surrounding the narrative. This is minor in comparison to Alfa grappling with what he’s done – still this aspect made me squirm.

In this novel, war is the primary evil. Diop creates an extremely humanistic approach to the high stakes setting as the themes throughout the novel push for more than a “black and white” interpretation of the First World War. The novel is set on creating a new “grey area” that history books have been neglectful of, allowing for a retelling of history from a voice we seldom hear.