When I think of modernity, I think of social exploration and excavation. Extending from the complexities of the Modern era, I envision a creative interpretation of human geology born from an interest in the diversity of cultural experience amidst a new age of progress. I think of layered histories. People, narratives – bound together, fused by time and proximity. I think of cities. Complex regions of existence where meaning is literally and figuratively calcified into the urban spaces we occupy. I also think of the symbolism surrounding the archeological process of cultivating this information and the significance of cultural artifacts. Because thinking about modernity compels us to review correlations between the past and how we live today.

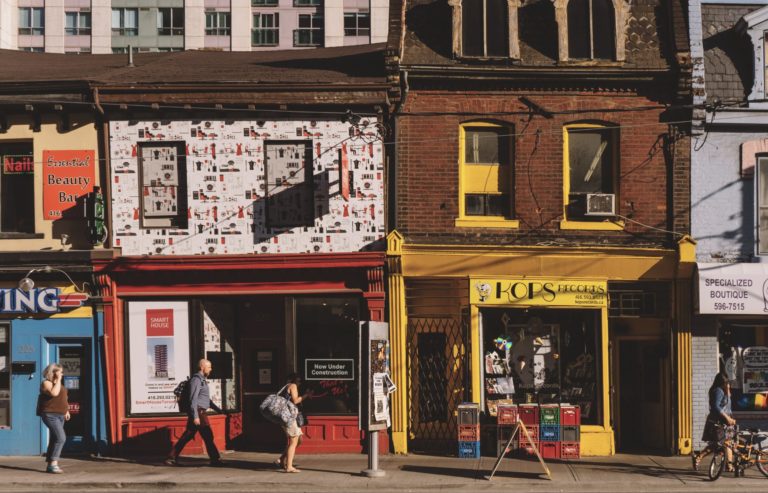

These types of meditations — those that engage tensions between the past and present in urban spaces — can facilitate seismic shifts in perspective capable of bringing people and cultures, separated by time, together in meaningful, sometimes unfathomable ways. I think of Toronto as being one of the best representations of a city able to engage these discussions, which is why it constantly inspires me.

In The Ward Uncovered: The Archeology of Everyday Life, Holly Martelle, Michael McClelland, Tatum Taylor and John Lorinc, along with their fellow contributors, relay their findings, reflections, and research conducted in Toronto during “one of the largest urban archeological projects ever carried out in Canada” (18). Located at Armoury and Chestnut Streets – within a region formerly known as St. John’s Ward – the Armoury Street Dig was initiated after land was excavated for the construction of a new provincial courthouse in 2015. This resulted in the discovery of thousands of artifacts dating from as far back as 2000 years ago to the mid-20th century. Revealing a dense and diverse spatial history—that includes the speculative geographical journey of an Onondaga chert spearhead and the landing experience of African American, Jewish Eastern European and Chinese immigrants and refugees, as well as many more groups—these objects also reflect the evolving cultural mosaic of the city today. Through recovered items such as an inscribed stone marker from the British Methodist Episcopal Church on Chestnut Street and rubber hat moulds from the Fashion Hat and Cap Company, we can regard earlier examples of socio-cultural enclaves, industry and even more narratives that ultimately reaffirm the diverse yet synchronistic nature of living in the city.

Lorinc and Taylor maintain that “[e]xcavated artifacts contribute to an understanding of heritage that combines fact and emotion, science and imagination [and that when] added to a historical narrative, archeology can confront or correct existing perceptions and long-standing biases” (24). Looking closer at objects of the past and gaining greater social and historical insight reshapes the larger cultural narrative we are a part of. It helps us recontextualize ourselves, our futures, and our creative interpretations of the regions we inhabit. The endeavors described in The Ward Uncovered force us to regard modernity’s exploratory impulse and the socio-geological reverberations of the world we are surrounded by as well as our place in it. They compel us to think of the spaces we occupy each day where we move in concert with each other. Creating a story, soon to be embedded in the city’s history. A story amongst stories layered like particles of sediment, fortified by generations of residents reminding us to look closer and realize that our history, much like our space, remains shared.

Originally published in White Wall Review 42: Special Issue (2019)